History is usually written by the winners, not by the losers, and the way in which the history of slavery has been represented, for the most part, is as abolition, the triumph of abolition. So we’re trying to think again about that way of writing the history and put the whole slavery business and the wealth it produced and the people who were involved in it back into British history.

If you read what we call against the grain of some of these histories, you can find the mediated voices of the enslaved.

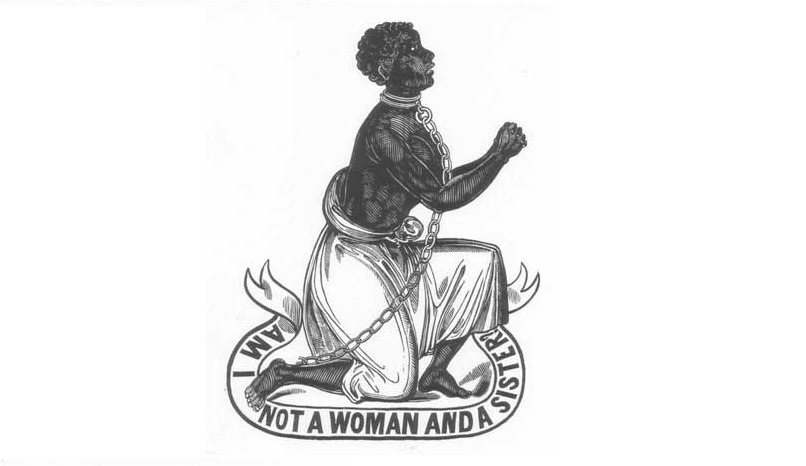

An interesting example of this would be the way in which a very famous narrative of a black enslaved woman, Mary Prince, was produced by the abolitionists as a form of propaganda in 1831.

This woman was living for some of this time in the area absolutely around Bloomsbury where her owner, John Adams Wood, had a house. Although it’s apparently in her voice telling her history, she tells it to a woman who transcribes it, and it’s then edited by the secretary of the anti-slavery society. So it’s made appropriate for an abolitionist audience.It’s telling a particular, it’s a particular way of telling the narrative, which can give us some access to the experience of the enslaved woman, but only some.

We can’t take it as simply authentic. That this is what Mary Prince said or thought. Trying to read between the lines is a very important way of trying to get access to black people’s experience, but this is work that it’s very, very important to do, and particularly important for women since, you know, they’re even less recorded.

In 1833, when slavery was abolished in British Caribbean and in Mauritius and the Cape, 20 million pounds was paid in compensation to the slave owners because they were seen as having lost what was called their property, the enslaved men and women who they had bought or who had been born in captivity on their estates.

And of that 20 million pounds, which was paid out of taxpayers’ money, nearly ten million stayed in Britain. So there were a very substantial number of slave owners in Britain who made substantial claims on that money and, therefore, had a large cash influx at that time.

The poet Elizabeth Barrett, who became Elizabeth Barrett Browning, was the daughter of a very significant Jamaican slave owner, and she had very, very complicated feelings about slavery and the slave ownership, and she was not sympathetic to slavery, but she was very well aware that the family money came from slavery, and, indeed, she inherited money on that basis. And she wrote a poem in the 1840’s which she wrote, in fact, for the American abolitionists called “The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point”, and in that poem, she tries to imagine being black.

So there are many powerful lines where in the poem, in the voice of an enslaved woman, “I am black, I am black.”And this is a woman who is raped by her white master,bares a child, cannot bear the fact that her child is the product of rape, kills the child, and calls on the enslaved to rebel.So it’s a very, very dramatic poem.Yet this woman, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, you know, who imagines all this, her own life is made comfortable financially by her family wealth, and she was not opposed at all to the principle of compensation.

She thought it was right that the slave owners were compensated because property was property, and if you lose property, it should be compensated. So that just gives us one of those complicated glimpses into what it meant to be totally implicated in the slavery business and yet to have very ambivalent feelings about it.It’s been hard for Britons to think about the extent to which slavery has shaped our history,and there are many physical remnants of that.The country houses that were built on slaving wealth,the art collections that were accumulated by slave owners,the ways in which sugar became an absolute essential part of the diet of the entire British population from the 18th century onwards,the ways in which British financial and commercial institutions have actually been built on Atlantic slave trade and slavery, and, of course, that’s a long time ago, but those are the roots. And then there’s the political legacies and the kinds of hierarchies of racism.

The ways in which contemporary racial thought has many in flexions from this long, long history. It’s those legacies that we’re pursuing through the 19th century, through our work on the compensation records, and where we want people to think about that because of the present, because of the present, and the ways in which these formations have been part of what it is to be a modern Britain.

By Ahmed Kotb