In the war-ravaged though officially at peace Democratic Republic of Congo, 12 percent of the population has been  raped. Nearly 50 women and girls are raped every hour.

raped. Nearly 50 women and girls are raped every hour.

“It’s true that we raped here. We found women because they can’t escape. You see her, you catch her, you take her away and you have your way with her,” one Congolese soldier told a reporter after a leave was ordered to “go and rape.” “Sometimes you kill her. When you finish raping then you kill her child. When we rape, we feel free.”

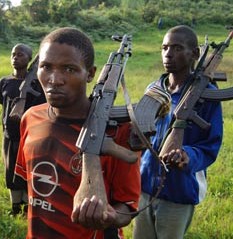

Soldiers of Congolese bands are frequently given leave by their commanders to “go and rape women.”

“How do you see someone who is hitting you in the eyes? How will you know someone who is inserting a gun barrel in your mouth?” one Congolese woman described the event of being raped by three soldiers. The woman had been raped before the incident with the soldiers, however, by a schoolteacher. The militia raped her two daughters as well, and afterward killed her husband.

Shamed, she was ostracized from her family and sought shelter with an aid organization. She has been raped three times since then.

1,152 women are raped every day–48 per hour–in the DRC, according to the American Journal of Public Health.

“Every day, they take the women and rape . You see a three-year-old child who has been raped. Why would they do that?” said film-maker Fiona Lloyd-Davies, whose documentary “Seeds of Hope” premiered at the Global Summit to End Sexual Violence in Conflict Tuesday.

“Every day, they take the women and rape . You see a three-year-old child who has been raped. Why would they do that?” said film-maker Fiona Lloyd-Davies, whose documentary “Seeds of Hope” premiered at the Global Summit to End Sexual Violence in Conflict Tuesday.

“[T]here is very little about sex there, it’s mostly about an experience of horror and power,” commented Rob Williams, the chief executive of War Child UK, a charity working to reduce rape in the Congo, on the issue.

Lloyd Davis said of Congolese rape victims, “I do think that women and girls expect to be raped, there is a sort of tired acceptance. More so in rural areas, where you need to walk far to get water, tend to your crops, or go to the forest and dig for cassava. The perpetrators could be militiamen from different groups, but it could also be soldiers from the Congolese army. It has become part of society, which is terrifying for women and girls.

The soldiers who commit these crimes are not always, but often, young men kidnapped and forced into the militia life from a young age. “They’re numb, they have been skewed, they have a different sense of what is normal. But this doesn’t mean they’re not aware of what they’re doing,” said Lloyd-Davies. Some soldiers express remorse, such as a man in “Seeds of Hope” who also said he would not admit his crimes unless his superiors were prosecuted. “They are the ones who sent us,” he said. “If those who committed these crimes can be arrested and judged, then that would be good.”

age. “They’re numb, they have been skewed, they have a different sense of what is normal. But this doesn’t mean they’re not aware of what they’re doing,” said Lloyd-Davies. Some soldiers express remorse, such as a man in “Seeds of Hope” who also said he would not admit his crimes unless his superiors were prosecuted. “They are the ones who sent us,” he said. “If those who committed these crimes can be arrested and judged, then that would be good.”

“Up until now, there have been very few trials, and the trials that we have seen have not been very effective,” Lloyd-Davies commented recently on the question of justice and accountability in the Congolese conflict.

She cited Bosko Ntaganda, an indicted war criminal, who had been sought by the International Criminal Court since 2006 for war crimes and crimes against humanity. In 2011 Ntaganda was in charge of 50,000 Congolese army troops and was working for the government.

Not only lack of accountability for perpetrators of rape, but shame of victims of rape also contributes to its perpetuation.

“There is a huge stigma attached to it,” said Lloyd-Davies. “Husbands and families often reject them. If they become pregnant, young women have told me that their family makes them choose between coming back to them and keeping the baby. Mostly the women seem to choose to stay with the baby, even though they often have difficult relationships with them, especially if they are boys.”

By Day Blakely Donaldson