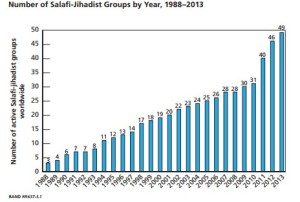

Since the founding of al Qaeda in 1988 by Osama bin Laden and two other foreign nationals in Pakistan, the terrorist organization has been successful in creating new branches and offshoots. A new study from RAND Institute says that in 1988 when al Qaeda was founded, there were three jihadist groups. In 2001 there were 22. Today there are 49.

The RAND report, “A Persistent Threat The Evolution of al Qa’ida and Other Salafi Jihadists,” was written by Seth Jones, the associate director of the International Security and Defense Policy Center at RAND for the Office of the Secretary of Defense. The report aimed to gauge the state of al Qa’ida and other Salafi-Jihadist groups, and based its finding on thousands of unclassified and declassified documents.

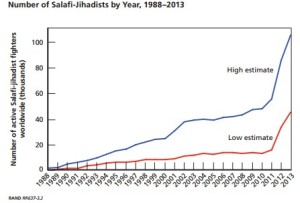

The report found that the US faces a serious and growing challenge overseas, although al Qaeda still kills many more Muslims than non-Muslims, as the number of Salafi-Jihadists (characterized by attempting to emulate the earliest Muslims [salaf – “ancestors”]) groups has steadily increased, particularly in North Africa and the Levant. The number of Salafi-Jihadists has also risen steadily, and jumped markedly in 2010. The number of fighters doubled between 2010 and 2013,

non-Muslims, as the number of Salafi-Jihadists (characterized by attempting to emulate the earliest Muslims [salaf – “ancestors”]) groups has steadily increased, particularly in North Africa and the Levant. The number of Salafi-Jihadists has also risen steadily, and jumped markedly in 2010. The number of fighters doubled between 2010 and 2013,  according to both high and low estimates.

according to both high and low estimates.

The number of differentiated–and sometimes separated–groups has surprised many in the West, who conceive of al Qaeda as a single group tied almost exclusively to terrorist actions. This is a misunderstanding, according to foremost experts in the field.

Tom Joscelyn, senior editor at the Long War Journal whose expertise is terrorism, commented on the Western misunderstanding.

Read more: Fascinating Look at ISIS by Analyst Before the Takeover, Reveals Predictions and Warnings

“I think there’s an intellectual confusion about what Al Qaeda is and how it operates,” Joscelynn recently said in an interview. “We still define–here in the West–we still define al Qaeda as a terrorist organization. We think big spectacular terrorist attacks are what they’re all about. They do do that. They are a terrorist organization. But they’re much more than that: they’re political revolutionaries who use terrorism as a tactic. And when you properly understand them in those terms, you understand they have designs on Libya, they have designs on Syria, they have designs on Yemen, Somalia, and other countries. They want to take control. They want power for themselves. That’s a very different dynamic than someone who’s just interested in flying planes into buildings.”

Al Qaeda members today have careers going back decades, building up their cadres of supporters–trained fighters–establishing training camps, and pushing their agendas forward.

The RAND study details examples of how Salafi-Jihadists have moved up and on from origins in al Qaeda, and become successful in many regions of the world.

One such example is the Egyptian Muhammad Jamal, who trained in al Qaeda camps in Afghanistan in the late 1980s before returning to his home country to become a top military commander for Islamic Jihad in Egypt. Jamal was released from prison in 2011, and took advantage of the permissive climate following the resignation of President Hosni Mubarak, to strengthen his position among a network of militants he had met before and during his prison time. With support from his relations within al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb and the Arabian Peninsula, Jamal and his group have been committing attacks against Egyptian, US and Western targets.

In countries such as Mali, Nigeria, Libya and Syria Salafi-Jihadists have similarly moved up the ranks and consolidated power and influence, and have also used customary political tactics to increase their authority. For example, a jihadist group that receives sanctuary in Libya, Ansar al-Sharia, has used a portrayal as a local movement to gain popular support. The groups has described their fighters as “our brave youth [who] continue the struggle,” provided security at a local hospital, publicized its charity work and used political slogans such as “Your Sons at Your Service.”

Other groups have pursued a priority of attacking Western interests–sometimes splitting from al Qaeda to do so, and sometimes joining with al Qaeda to do so. Mokhtar Belmokhtar’s al-Murabitun, which operates in North Africa and Africa, split from al Qaeda in 2012 to pursue such attacks. In Tunisia, an Ansar al-Sharia partnered with al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb for a similar cause.

In a conference earlier this year, Joscelyn stated a conclusion about al Qaeda. “Al Qaeda set out in 1988 to spark a political revolution to inspire jihadism around the globe. They’ve succeeded. We’ve still not come up with a real strategy for containing or combatting that across the board.”

By Day Blakely Donaldson