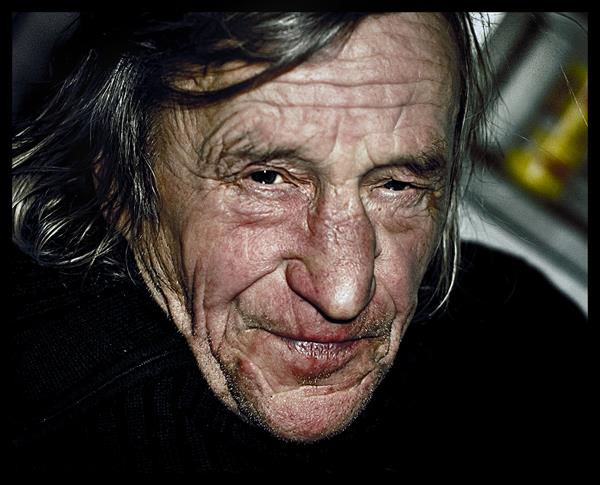

Photo document by Paris photographer Andrea Peter Fly

The French Charity “Les Morts Dans La Rue” (the Dead in the Streets) recently announced that during 2013, 454 homeless individuals died in France. Contrary to common belief, as many of those deaths occurred in the summer as in the winter.

Between 2001 and 2012 the number of individuals living on France’s streets increased by 50 percent. The estimated total number of homeless in 2012 was 141,500; of whom 10–15, 000 reside in the Paris region.

Why does homelessness happen to certain people? Is it their own fault or even their choice? Is a homeless person weaker? Less intelligent? Less fortunate? Is their homelessness a consequence of substance abuse that’s gotten out of hand? A consequence of illness? Or divorce? Could this actuality happen to any one of us? Are these people regular human beings, with the same fundamental needs and desires as our own, or are they in some way different?

Now that we are familiar with the statistics, why not let us engage the individuals concerned and listen, without judgment or preconceptions, to what they have to say about their pasts and their terrifying present.

Here are their stories.

“Life gives us three options; be a blind sheep, try to create your own path or give up. That homeless guy you see on the metro, with a bottle in his hand, he’s just a man who has given up. He doesn’t even have the strength to stay clean. It’s just a guy who is waiting for death, nothing else. Personally I’d prefer to die standing up than live kneeling down.”

Law graduate and former manager at Leroy Merlin on a salary of 3700€/month, Ali became homeless after his divorce. Ali’s situation came about somewhat by choice. Following his divorce he decided to leave his apartment and belongings to his ex-wife and son, allowing them to stay in Paris and affording him the opportunity to continue seeing his child. This was three and half years ago, and he has remained homeless ever since.

In January Ali managed to find a new job and has now been working for three months. Receiving a salary statement, he hopes to soon be able to begin his search for an apartment. Ali’s new employer decided to give him a chance, presenting him with at what is both a great challenge and a responsibility that he hopes to honour. Just the fact of his having a job has already provided Ali with a sense of dignity.

Having a family that is supportive and helpful is a good thing when things are going well, but Ali doesn’t want any help. His situation is his own responsibility and no one else’s. He put himself here and now he needs to find a solution on his own.

“We only learn in fear. When you find yourself on the street without any distractions, like money, TV, or anything else, the only thing you have left is yourself. It’s like looking in the mirror naked. You need to take a look at what you have and work out what you can do with it. A complete searching of the soul”.

Those passers-by on modest monthly salaries of €1000-€1500 are fully aware of the fact that they are just one step away from Ali’s present situation. Their life too is a struggle. Sometimes a homeless individual who receives the Active Solidarity Income has more money at the end of the month than a working individual who’s paying the bills. “This is the main reason why they avoid us, they don’t want to see what might happen to them one day.” Destruction is easier and faster than construction. You can fall in a second. Rising up takes time.

In Ali’s day-to-day life, solitude is the heaviest burden. He doesn’t visit the various public shelters anymore. “its just not safe and often brings more problems such as fighting, theft and a lack of respect from employees of the shelter”. Neither the state nor the masses are really interested in the points of view of Ali and those like him. Unfortunately most homeless are not ready to raise their voices and be heard. This is why “SDF” (sans domicile fixe) takes the sole form of numbers and statistics; that people may avoid for as long possible.

Ali’s dream is to start his own association representing the homeless with a figurehead who is themselves homeless. One who knows what they are talking about, who lives it, who can be a united voice and communicate with the media and government. He also wishes that people could look more with their hearts instead of their eyes, have a bit more empathy, reaching out a hand is always better than taking a hand.

Ali stays positive and hopeful. He has to. If he loses faith then it’s over, the beginning of the end, where you end up like that drunk smelly guy on the metro with a bottle in his hand, who just doesn’t care anymore.

Henok, 25 years old

“I knew that there are a lot of black people here in Paris, that’s why I came here.”

Henok is of Ethiopian origin and has been in France for five months. He is one of the 500 refugees living in a tent outside the train station Gare du Nord, in the central of Paris. All refugees in this “illegal camp” are of African heritage: Algeria, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Libya, Sudan and so on. As most others he came by boat: from Sudan to Libya, Libya to Italy and by bus to Paris where he, like many others, was dropped off at Gare du Nord. Some refugees choose London as a destination others come to Paris. The main reason to why he chose Paris, is he thought he might feel more at home here, as Paris is known for it’s African population. Henok is hoping to get a permanent residence permit so he can stay; going back home is not even an option. Being part of the Oromo population, a population ruthlessly targeted in Ethiopia, returning equals dying. Being homeless in Paris is not easy, and not what he expected or imagined, but he has no other choice. He is grateful for every second he gets to spend in France, and tries to have a positive outlook. The extreme lack of accommodation in a country as well-developed as France, one of the most powerful states in the world, is for Henok incomprehensible. The French population is not to be blamed, he says. “People do come and try to help, but mainly French Arabs. They come with food, clothes, sometimes even money, and white French people usually bring us tea.”

The camp is usually quite calm, no fights, and no problems. The police never come, some charity organizations every now and then, and of course the media. The media is extremely present, and non-wanted, as despite their constant attempts to approach the refugee “camp” (often ruthlessly and with disrespect), nothing ever changes.

Constantin, 70 years old

“I’d rather live on the streets of Paris than return to Romania.”

Constantin receives no pension from Romania, despite having worked there as a driver in the agricultural sector for 38 years. It’s for this reason that he chose to come and try his luck on the streets of Paris. Having no family, Constantin arrived in France three months ago and hopes to stay for as long as possible.

To survive, Constantin begs for money. He also receives alms from the local churches as well as charity from Emmaus; a French nationwide solidarity movement against poverty started in Paris.

On account of his age, and lacking a firm grasp of the language, Constantin cannot work. He harbors no wish to depart. Difficult as life in Paris may be, it is better than life in Romania. His only wish is to be able to stay for as long as possible.

Frédérique Nghiem, 45 years old (L’un et L’autre)

“You must never lose hope.”

Frederique is accommodated by Chapsa (the largest homeless shelter in the Ile de France region), where the atmosphere is not always pleasant and the organization itself is quite strict. For almost 10 years, she has been visiting the association L’un et L’autre (Porte de Villette, Paris) for her daily meal, as she has no other option to feed herself. Being under public care, she receives €80/week from the French government for which she is extremely grateful. She considers herself lucky.

Following a life-threatening illness and more than eight operations, she has never been able to adapt to a working life. If she has somehow retained the strength to go on, staying positive and believing in a better future, it’s all thanks to her man. “My little man,” she calls him with a big smile on her face.

Despite her difficulties, Frederique remains optimistic and positive; believing in a better world for everyone. “You must never lose hope.” Her great regret, is that of having a family who want nothing to do with her. If there is one thing she could wish for, it’s to one day make peace with her mother and sister, and be accepted just the way she is.

Helmut, 59 years old

“It’s my choice, this is what I want.”

Herman is of German origin. He is divorced and has a son. Having obtained several degrees, his two main professions in the past were that of mechanic and slater. Today he is a street artist, painting and drawing on the streets of Paris. A year and a half ago he decided to sell his studio and apartment to buy a caravan, in which he’s been living since. It’s a mode of life he is very content with; without difficulties, but to the contrary, evoking a sensation of freedom.

Helmut can be found at Palais Royale in Paris, where he spends his days painting. He doesn’t accept any financial aid from the government, nor from the various associations in Paris. He lives off the money he makes from his art and doesn’t complain; he appreciates the generosity of his clientele. His plan is to make enough money to be able to afford a house one day, whilst continuing to create his works, painting in the streets.

Hrisw, 57 years old

“How do you feed four children with €10 a month?”

Of Bulgarian origin and nationality, Hrisw had resided in France for 3 months, and was sent back to Bulgaria on March 20, 2014.

He came to France because of the Bulgarian mafia and the poverty this causes in his country. A father of four children, he finds it impossible to support and feed his family with the € 10/month he earns back home. The streets of Paris remain more profitable.

As a construction worker in Bulgaria, he doesn’t earn enough to survive himself, let alone enough to support a family. Despite a willingness to work for an income, this remains difficult in France; impossible even without the language skills necessary or a fixed address.

Hrisw spent three months in Paris begging for money on the street. Now he returns home with the money he’s gained to try to help his family.

Janous, 33 ans

“I don’t go to the public shelters anymore, mainly because of religious conflicts. As a catholic why don’t I have the same right to practice and express my religion, as a Muslim has?”

Of Polish origin, a painter, Janous has been in France for five years now, also homeless for five years. Arriving in France, he lost all his documents, passport, everything, and has never taken care of it. To survive, he gets his daily hot meal at Soupe Populaire. In the daytime he picks up out-of-date products from the local super market and goes through the garbage. To cope psychologically he drinks constantly. It has become a way to survive, and to sleep. Sleeping not being drunk is not even imaginable. The heaviest burden in his every day life is the rain. He doesn’t mind the cold, as he usually sleeps on the grid, which keeps him warm, even burns his hand sometimes, but nothing protects against the unpleasant rain. The shelters are mostly dangerous and create problems more than anything else. Janos doesn’t go there anymore, and the main reason being religious conflicts with Muslims. If a Muslim can pull out a rug to pray on whenever and wherever why isn’t he allowed to put his cross up on the wall? This being a regularly occurring issue, he has chosen to avoid the shelters, and sleep outside.

Despite the fact that each problem has a solution, Janous is skeptical about the future.

“We’re all human beings. It’s extremely rare that you hear of a homeless person committing serious crimes: theft, physical attack, rape or whatever it may be. It’s often also the reason to why a person becomes homeless, because they refuse to walk down that path. If we say hello to you, the least you can do is smile or respond — we’re not evil and we don’t deserve to be treated like we’re invisible.”

The daughter of an alcoholic mother, Laure spent her childhood in 21 foster homes. At the age of 18 she found a non-declared waitress job. When they let her go, not being able to pay rent, she was thrown out despite the fact that the apartment belonged to an association. Laure called out to her friends on Facebook to find a place to sleep until she got back on her feet, but she was left stranded. She has been homeless since October 2014. Dangerous as the streets may be, especially for a young girl, she considers herself lucky to have found friends in the same situation who help and support her no matter what. At the age of 19, she has already gone through a phase dealing with drug addiction, but realized that this path would only stop her from ever evolving and moving forward. Alcohol has never been an issue, due to her experience with an alcoholic mother, whose footsteps she does not wish to follow. In France, under the age of 25 one has no right to any financial aid. Her social worker, as well as all the different associations in France, they do provide a help, to survive from one day to the other, with clothing, food or a bed for the night. Unfortunately no one can or will help you to advance, mover forward, finding a job or a flat.

To survive, she begs for money, and often finds people’s generosity quite limited. There is more of a curiosity, and if they give money or not depends on how much her story moves them. The worst moments in her everyday life are often represented by the way people behave, react and look at her. When you’re homeless you feel invisible, as people won’t even respond when you say hello or even look at you to recognize your existence. Laure stays positive and certain that her luck will turn around. After having hit rock bottom, one needs to rise, but respecting all the different stages, and not too fast, if not a relapse is inevitable.

Marcel, 63 years old

“There is nothing worse than when you daughter passes you in the street and is so ashamed that she won’t even say hello.”

Back in the days when life was good, when he had lots of money, lots of friends, Marcel was a cabinet-worker. The descent began after his divorce, which was caused mainly by the difference of social status within the couple, and which over time widened the gap between him and his ex-wife to the point where he felt he had to leave to survive. followed by 10 years of being homeless, alcoholism, mental break down, even attempted suicide. Today all of this is behind him, and he has a roof over his head. With his pension he pays his rent, and begs for money to cover other expenses, like food. Begging for money is nothing to be ashamed of. Back in the 17th century this was a proper profession. His two children laugh with him, except for the 3rd child, a daughter who is so ashamed she won’t greet him on the street, which is his biggest grief in life. In general he finds people are generous, interesting and quite pleasant, which helps him to stay positive for the future, not losing hope. If he can give one advice to others, he would ask everyone to listen to their children and their hearts. There is nothing more important in life, than that.

“Having a social life and staying active is essential to survive.”

Salesman and building painter, he has been retired for 6 months now. Marcel’s pension is 417.33 €/month, which is even less than the French Active Solidarity income that everyone of age of 25 has a right to for five years. His rent is 125 €/month, an apartment he received thanks to his persistence at the town hall. After having spent one year and three months on the streets. His situation unraveled after his wife’s death. The family, her family, blocked their joint account, and he was asked to leave the apartment. The day of the ruling his social worker was sick, so, with no one to defend him, he became homeless. Being out of work at the same time, rising from this situation became extremely difficult. Still today, he does need to make some sacrifices to be able to survive with his limited resources, with water and electricity being the most important elements to save money. In the morning he takes a cold shower, and reuses the same water to flush the toilette. Some days he still has to go through the garbage. The association La Soupe Populaire provides him with his daily meal, and has done so for quite a few years now. Having a social life, staying active, having someone to talk to is what gives him the force and motivation to go on.

Pascal, 52 years old

“Don’t look at me with such contempt. Yesterday I was in your shoes, with money, a house, everything you have, and tomorrow you might find yourself in mine. There are no guarantees in life.”

A former military officer, homeless for three months now, Pascal is waiting for his Active Solidarity Income papers to be able to launch the administrative procedures for a professional reconversion. At his age, it’s not easy, and the procedures are long and tiring. His situation is a result of a separation. He quit the army so he could invest in his home life and started working for his father in law. Unfortunately, when the relationship fell apart, so did his job. He found some temporary labour positions, but after his accident, hurting his knee, he was no longer able to do the same physical work. Despite his savings, after a while he couldn’t pay rent and became homeless, the downfall went almost from one day to the other, extremely quickly. Thanks to different associations, like Action Froid, who reclaim expired products from supermarkets, he manages to survive. With his tent mates and from the other tent down the street, they help each other as much as they can. The city provides public showers, toilets and laundry mats.

They never had any trouble with the local police; the tent is registered. As long as the neighbours don’t complain they are left alone. To go on, to survive, one has to take the best of each day and nourish it, even if the condemning looks of certain ignorant strangers are not always easy to bear. Pascal stays positive and puts all his hope in the hands of the city of Paris, to help him advance and progress.

“I’ve never seen such charitable acts anywhere else as can be found in France. It’s really beyond me that people accuse the French of being racists. Helping others in need is not what I would call racism.”

André is a lawyer of Guinean origin who has been in France since November 2014 with a pending asylum request. He came to France to be closer to his two daughters. His ex-wife left him suddenly in 2003 to come live in France. Today, the older daughter is living with a foster family, where the authorities placed her after having been abused and beaten by her uncle. The younger daughter is still with her mother, but with a social worker. André is very grateful to the judicial tribunal for always keeping him informed concerning his girls. Not having been able to come sooner for legal reasons, he currently has the right to stay in contact with his girls via phone calls and visits. Meanwhile he has a roof over his head for three months in a shelter, and is nurtured through the association L’un et L’autre. He has nothing but gratitude for the French government for letting him come here and fight for his family. After having spent five years in Belgium, he insists on accentuating on the fact that there is no other European country with such beneficence as the one in France. No where else will you see thousands of people in need, being fed, for free, or marauding, where people will circle the streets looking for others in need, to help, which is something absolutely remarkable. This beneficence is what saved his life and what keeps him away from hunger, as well as giving him hope for the future. To not be able to work, spending the days doing nothing is his greatest challenge, but André stays positive and is eager to see the day when he can exercise his profession, as well as going back to University to earn his Ph.D.

André, 68 years old

“After having survived 40 years on the street, I don’t care what others think. Everyone thinks whatever they want.”

A former metallurgist, André has travelled the world. He has been homeless for 40 years now, and in Paris for four years. André doesn’t receive governmental aid, but unlike many others it’s his choice. The association Action Froid does provide him with clothing and alimentary aid. He regularly asks for books to read. Even though he dreams of having a roof over hid head one day, his life has brought a sensation of freedom. André feels liberated, of everything: others’ opinions, the state, and the daily obligations. When asked, what brought him into his current situation, he stresses the fact that it doesn’t matter anymore. What matters is that he is still alive, remaining positive.

Raphael, 50 years old

“The main problem here is the state, not the people. No comparison to the Canadian system, where citizens in need are really helped and protected.”

Of Canadian origin, former tourist guide, Raphael came to Paris in 2006. Having gone through a burn out, he decided to travel, arrived in France after a short visit in Switzerland. Arriving, he lost all his official documents, his passport, his birth certificate, everything, which subsequently resulted in depression and a life without a roof over his head. Ever since then, he has never had the force to deal with the French administrative process to obtain a new passport. For a new passport he needs a birth certificate, and the process is just too complicated and tiring, even though his single wish is going back home. Being a foreigner, without papers, officially Raphael doesn’t exist anymore, and has no rights whatsoever, just one of many who don’t show up in the statistics. He goes to Soupe Populaire for his daily meal, and his one and single pleasure remains smoking a cigarette, when he is lucky to get one, tiny glimpses of pleasure to help bear with the cold and the noise from the street.

“I would never beg for money, trying to keep my dignity. I would much prefer having a job and be working.”

Never having had a family, being an orphan, Stephane still managed to obtain several degrees as well as found and manage companies. The last one was specialized in electricity, plumbing and ironwork. Due to a professional error on his part, not having paid the VAT for the company, he went bankrupt with compulsory liquidation. In less than one year, he lost everything and became home less. Homeless for three years now, and fully aware that this is purely a consequence of his errors. This does not stop him from trying to re-launch his professional activity, with the assistance of a lawyer. Not having a roof over his head does not make it easier, neither does his alcohol abuse. After a heavy period of drinking, a bottle of vodka a day, he is trying to pull it together. Realizing that despite the momentary psychological relief that alcohol brings and the simple fact that it helps to keep warm during cold weather, as long as his consumption stays intensive it will restrain him from moving forward in any way. As the shelters with 300 beds are dangerous more than anything else, with fights and thefts, he prefers staying outside. Thanks to the association La Soupe Populaire, he gets his daily warm meal. Stéphane stays positive, hopeful, and does not want to lose his dignity. He would never allow himself to beg for money — it’s not a profession. The social worker in charge can help him with meal coupons or with a place in a shelter but unfortunately she does not have the capacity to provide him with assistance that would help him get off the streets or progress in any way.

Sylvain, 31 years old

“I may be an addict, but I’m not a squealer.”

Former mechanic at Mercedes Benz, currently a seasonal winemaker, he has been homeless for 12 years. The first two years he spent on the streets, and has managed to squat for 10 years. Sylvain has a truck that he uses for his work, but that currently is being repaired, so to survive he has no choice but to beg for money, he doesn’t accept any governmental aid. The family he has doesn’t bring any help in his every day life. Twelve years ago Sylvain was a mechanic at Mercedes Benz, where he also sold drugs to the other employees, including all his bosses. One day he was asked to denounce other employees committing theft in the company. As he refused, he was forced to resign, either that or be reported to the police as a drug dealer. Not having an income, or not having the right to unemployment benefits as he resigned, he couldn’t pay his rent and became homeless three months later.

Psychologically, his two dogs are a great support, but don’t recompense for the frustration, distress and anxiety of spending his days doing nothing. A day of begging for money on the street usually results in 10-20€. Raphael doesn’t understand the lack of help from the state, all those empty apartments nation wide — why aren’t they used to house and help people in need? Because there is no money in it. At Troyes, where he spends most of his time, begging for money on the street is fined with 35€. All he is hoping for is to one day having a “normal” life, with a job, a girlfriend, just an ordinary life like everybody else. Sylvain stays hopeful, but is losing faith in humanity, more and more for each day. As people pass him on the street, he sees on an every day bases the lack of empathy, mercy and just a growing selfish self-centred mentality, which he doesn’t understand. After all, we are all just human beings.

Wenceslas, 46 years old

“The government tries to save 1,700,000 € by retaining the Active Solidarity Income from people who are entitled to it. The number of people who never manage to obtain it is absolutely ridiculous.”

Wenceslas is a former warehouseman, salesman, plumber and fire security guard, unemployed and homeless since 2008. He was dismissed from his last position due to the merger/integration of Lagardère, also partly responsible for the collapse and bankruptcy of Virgin Megastore. As his apartment building changed owners, not having the resources to purchase, he became homeless.

To survive, he collects out-of-date product from supermarkets, always in limited quantity. He tries to keep busy, by working out in sport facilities that are free. His petition at the European Court of Human Rights is something that keeps him busy and motivated. This is the second petition, in the last eight years. The first one was a victory, “The Winter Plan,” obtaining the right to spend nights in different indoor arenas, as well as a cessation of chase by police officers. Unfortunately the Minister of Housing reactivated the chase. With his second petition he hopes to be able to put an end to this unfortunate chase, which is one of the greatest challenges of not having a home. In winter the cold weather and rain requires more belongings to be able to stay warm. Belongings they can’t hide or put aside, so getting chased by the police as you’re trying to wash up is not very pleasant. Unfortunately, Wenceslas doesn’t even receive his Active Solidarity Income despite having gone through all the trouble of respecting the different administrative procedures. This defeat and challenge won’t stop him; Wenceslas will continue his battle for his human rights no matter what.

“The solitude is unbearable.”

Xavier describes himself as “a sick man walking the streets.” He suffers from a mental illness, where he feels condemned without knowing why. He is a prisoner of language, a prisoner who has always been excluded from a social life, starting from his childhood, especially with his brother. The streets of Paris have been “his home” for almost 30 years now. Losing his apartment, feeling rejected, excluded from society, he gave up all hope and didn’t follow through with his plan to work with the elderly. Xavier’s whole life is described as a long journey of pain, suffering, and a full exclusion. His living hell continues on the streets, with loneliness so profound it’s almost unbearable. No one talks to him, he feels invisible. Xavier is not receiving any help from the different association nor the government. With his illness, he has no hope for the future, the only thing he hopes for, dreams of, is to have more human contact, on regular bases, someone to talk to every now and then.

“One is the Other” in English, L’un est L’autre is a non-profit organisation feeding people in need. Their main purpose is to serve lunch Saturday and Sunday every week to more than 1,200 people. Donors and the state fund the association with a yearly budget of 60,000€, which is divided between the two. This amount corresponds to 1€/meal. As clearly indicated by the name, the approach is that “the other,” the one who is suffering, is just another version of our selves; all human beings are equal. The association consists of 60 volunteers, and the budget restricted to 600 meals served/day, but the goal is to improve the quality of service, by serving proper home cooked meals and being able to increase the number of beneficiaries. This requires an important increase of budget, meaning a greater need of donations and stately subventions.

La Soupe Populaire

Translated, Soup Kitchen is a term which has existed since the 18th century, but became more prominent in the 20th century during the Great Depression. Masses of unemployed workers were fed for free in Europe and in the United States to prevent mass death. About 100 years ago, in Paris each arrondissement had it’s own Soup Kitchen, 20 in total, today there is one left, in the 6th.

This soup kitchen serves hot meals, with soup, based on natural products, 6 days a week, Monday through Saturday. The association is supported solely by donations from citizens and local merchants. Thanks to their generosity, 33,000 meals are served each year, at a cost of 11,500€, which comes down to 3.5€ per meal. Even if the number of beneficiaries increase each year, 800 more in 2014 than in 2013, the amount of donations decrease at the same time, 5,000 € less in 2014 than in 2013. Volunteers serve the meals — about 40 individuals that come to give a helping hand on regular bases.

A non-profit organisation, translated as “Cold Action,” launched in 2012. It was initially created to provide homeless people with supplies to keep warm and stay alive during the winter season. The association was created by Lauren Eyzat, using social media — in particular Facebook — to launch the organisation, with saw an immediate response and action from other citizens. The first action on the field, the streets of Paris, was taken on the day of foundation. In three years it has developed into a nationwide organisation with more than 100 volunteers in Paris as well as in other French cities. Citizens and companies contributed to a budget of 18,000 € for 2014. Thanks to free publicity, the association has already reached its financial target for 2015. All the funds go to the homeless, providing them with the supplies they need: food, covers, clothing and even books. The beneficiaries have the opportunity to “pass an order,” and if possible have their needs met. There is a clear increase in the number of beneficiaries, but also of the association’s budget — which means more help to more people. The distribution takes place Saturday night every week, when a large team divided into approximately 8-10 cars cover the whole city. As the volunteers are present on a regular bases, they manage to have closer and more personal contact with the people on the street.

By Andrea Peter Fly