A new joint collaboration between Tel Aviv University, Columbia University’s Medical Center, and the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) has demonstrated that life events can effect the genetic heritage of an organism’s immediate descendants. The Columbia team was able to show that transgenerational memory is passed on through an organism’s short RNAs for at least three generations.

“It shows that our experiences shape our inheritance… and that’s there’s a memory of our ancestors’ lives,” Tel Aviv’s Oded Rechavi, lead researcher on the project, told The Speaker.

The study, “Starvation-Induced Transgenerational Inheritance of Small RNAs in C. elegans,” was completed by Leah Houri-Ze’evi, Sarit Anava, Wee Siong Sho Goh, Sze Yen Kerk, Gregory J. Hannon and Oliver Hobert, in addition to Rechavi. The study was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical institute and was published in the June 10 edition of Cell.

The study, “Starvation-Induced Transgenerational Inheritance of Small RNAs in C. elegans,” was completed by Leah Houri-Ze’evi, Sarit Anava, Wee Siong Sho Goh, Sze Yen Kerk, Gregory J. Hannon and Oliver Hobert, in addition to Rechavi. The study was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical institute and was published in the June 10 edition of Cell.

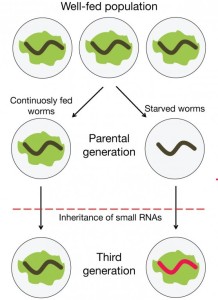

In its research, the team demonstrated that drastic environmental changes, such as famine, can cause genetic changes that are passed down through at least three consecutive generations.

The team demonstrated this using roundworms. The team starved roundworms for six days and examined their cells. The starved roundworms were found to have developed a specific set of small RNAs.

Small RNAs are a type of non-coding RNA (ncRNA), functional RNA molecules that are not translated into protein (as are DNA). Many ncRNAs have been newly identified in recent years, and have not yet been validated for their function. Small RNAs are involved in various aspects of genetic expression.

“Small RNA-induced gene silencing can persist over several generations via transgenerationally inherited small RNA molecules in C. elegans,” stated Rachavi. Starvation induced changes in the roundworms’ small RNA were inherited by subsequent generations. The genetic inheritance took place apparently independent of DNA involvement.

Based on evidence of human famines and animal studies, it had long been suspected that starvation can affect the health of descendants, but the means by which such genetic inheritance was conveyed was not known.

“[E]vents like the Dutch famine of World War II have compelled scientists to take a fresh look at acquired inheritance,” said Oliver Hobert, PhD, professor of biochemistry and molecular biophysics and Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator. Animal studies have been conducted showing that, like humans who give birth during famine, animals such as rats can be caused to produce thin or obese offspring.

Roundworms were used in another small RNA-related study in 2011, when they were used to show that virus immunity developed during a parent’s life could be passed on to offspring for many generations through small RNA viral-silencing.

Hobert suspected that the small RNAs were somehow finding their way into the worms’ sperm and egg cells. “When the worms reproduced, the small RNAs could have been transmitted from one generation to the next in the cell body of the germ cells, independent of the DNA.”

How small RNAs were entering germ cells, and what types of biological experiences were registered by small RNA changes, Rechavi told The Speaker, “is a completely uncharted area.”

Rechavi said that the response to an organism’s environment was, however, “not necessarily only dietary related. In theory… any response that would produce a strong systemic small RNA response could be heritable. It’s not clear exactly how small RNAs find their way to the germline, but in worms several genes that enable cell-to-cell transfer of small RNAs have been discovered.”

In Rechavi’s previous work he has demonstrated that human immune cells, such as T or NK cells, can exchange small RNAs with other cells, and that some small RNAs can be found circulating in human blood.

“In general, I would suspect that it would be worth ‘memorizing,’ or producing a heritable response,” Rechavi told us, “cues which are really important for the survival of the organism.”

The implications of the study include that the biology of inheritance is more complicated than previously thought.

“[They] suggest that we should be aware of other things—beyond pure DNA changes—that may have a long-term impact on the health of an organism,” said Dr. Hobert. “In other words, something that happened to one generation, whether famine or some other traumatic event, may be relevant to the health of its descendants for generations.”

The study has also been said to give weight to the long-dismissed Lamarckian theory of genetics, which proposed that organisms adapt to their environment and pass on adaptations to offspring. Lamarckian genetics has traditionally been contrasted with Darwinian genetics, which theorized that all mutations were random, and the randomly mutated offspring were selected by nature according to their success surviving and reproducing.

Next for Rechavi and his team is to further pursue an understanding of the effects of environment on genetics. “We are testing how stable these effects are,” Dr. Rechavi told us. “exactly how the small RNAs are produced, and which regulated genes are most important in the process. We are also interested in examining the generality of this mechanism. This could be an important mechanism that acts side by side along with the traditional DNA-based inheritance mechanism.”

By Day Blakely Donaldson