Two marine researchers have published a report on two prominent near-bottom fish species of the northern seas, looking at how the two species fared in the warming waters of the past decade. The researchers looked at Bering Sea walleye pollock and Atlantic cod, and proposed that the differences in how the two species fared may be indicative of how other species will variously thrive or suffer during global warming.

The northern waters of both the cod and the pollock have warmed over the past decade, but one of the species appears to have prospered, while the other has diminished. “These response patterns appear to be linked to a complex suite of climatic and oceanic processes that may portend future responses to warming ocean conditions,” stated the researchers.

The report, “Distinct impact of tropical SSTs on summer North Pacific high and western North Pacific subtropical high,” was written by Anne B. Hollowed of the Alaska Fisheries Center’s National Marine Fisheries Service and Svein Sundby of the Institute of Marine Research, and was published in Science Magazine.

The report, “Distinct impact of tropical SSTs on summer North Pacific high and western North Pacific subtropical high,” was written by Anne B. Hollowed of the Alaska Fisheries Center’s National Marine Fisheries Service and Svein Sundby of the Institute of Marine Research, and was published in Science Magazine.

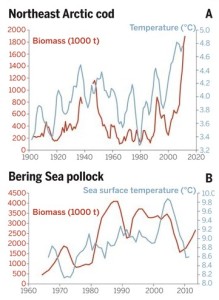

The report explained that Atlantic cod stock biomass has steadily increased since the 1980s, paralleling an increase in northern oceanic tempertures. Atlantic Cod, which spawn in the southern end of their territory, are thought to require warm temperatures to produce strong year classes. “During warming phases,” the report read, “the spawning stock biomass gradually builds up and the cod spawn rather north,” whereas in cooler phases spawning takes place further south. A similar trend of increasing fish stocks accompanied the warming period between the 1920s and the 1940s.  The recent success of Atlantic cod stocks is thought to be the result of warmer weather, in addition to the effects of fishing limitations.

The recent success of Atlantic cod stocks is thought to be the result of warmer weather, in addition to the effects of fishing limitations.

On the other hand, Bering Sea pollock–the largest fish stock in the northeast Pacific Ocean–declined in the early 2000. The stock began rising again before 2010, but did not reach pre-2000 levels.

The habitat and diet of pollock is thought to account for the difference. Bering Sea pollock feed throughout the middle and outer shelf regions and generally avoid bottom waters below 0 degrees Celsius–and so are usually found in the southern Bering Sea. The fish expand across the shelf in warmer years. The pollock stock is made up of several age groups, each of which has been affected by prey availability and the ability to accumulate winter stores of energy.

The pollock are thought to be affected by temperature most significantly in the first year of their life–due to the effects of temperature on their first summer.

The pollock are thought to be affected by temperature most significantly in the first year of their life–due to the effects of temperature on their first summer.

The report concluded, “The response of seafloor fish species in the border regions between the boreal and Arctic domains to climate variability may provide clues to how future antrhopogenic climate change will influence fish stocks and marine ecosystems at high latitudes.”

The report also made more specific predictions about the future of Atlantic cod and Bering Sea pollock. The cod, which have already reached the shelf break and the deep polar basin, can advance no further north, and so may now advance eastward along the Siberian shelf as new habitats open up due to the loss of sea ice at the Siberian shelf and the Northeast Passage. The pollock face an uncertain future, because the suite of interacting processes that govern their health is more complex, and because sea ice is expected to continue to form in fall and winter, leaving a cold remnant in summer, making the cold pools inhospitable to the fish.

by Sid Douglas