What is the state of lobbying in Europe? How transparent is it? Is there a clear and enforceable code of conduct for lobbying activities? How diverse are the voices affecting decision making?

In their latest report Lobbying Europe: Hidden Influence, Privileged Access Transparency International (TI) answers these very questions.

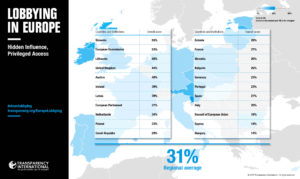

The study looks at the practice of lobbying and its regulations within 19 EU national governments and the three main EU institutions: the European Commission, the EU Parliament, and the EU Council.

It is underpinned by three research criteria:

- Transparency – are interactions between lobbyists and public officials transparent and open to public scrutiny?

- Integrity – is there a clear and enforceable code of behaviour that ensures lobbying is conducted ethically?

- Equality of access – how diverse is the range of voices affecting decision-making, how accessible is the political system to a wide range of citizens?

With some 15-30 thousand lobbyists regularly walking in the corridors of EU institutions, the lobbying industry in Europe is not just thriving but is becoming increasingly sophisticated. It includes professional lobbyists, corporations, private sector representatives, trade unions and law firms, and also NGOs, think-tanks, academics and faith-based organisations.

Underpinned by transparency, integrity and equality of access, lobbying can be a democratic tool, as multiple views can help shape the political debate and agenda in ways that are richer and fairer to the millions of people who will be ultimately impacted by the decisions taken. Legislation on food labeling, pesticide use, carbon emissions, smoking bans, recycling targets, and gay marriage are all examples of lobbying as a force for good.

However, in their latest report TI show us why the practice often still has a rather seedy ring to it.

The study finds ineffective and piecemeal lobbying regulations across EU countries and institutions overall. It finds that only seven (Austria, France, Ireland, Lithuania, Poland, Slovenia and the United Kingdom) of the 19 countries investigated have some kind of lobbying regulation in place, but even then regulation is either poorly designed or not properly implemented.

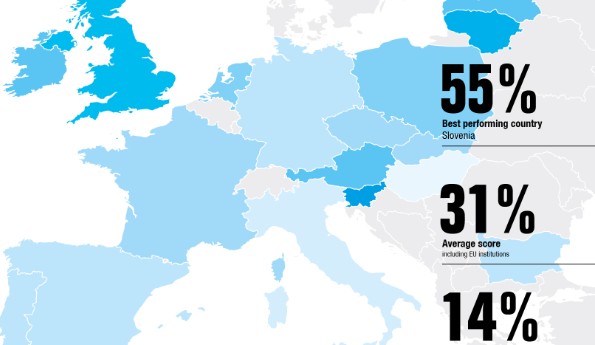

When measured against international standards and best practices, the 19 EU countries and EU institutions together only scored an average 31 percent for the quality of their promotion of transparency, integrity and equality of access in lobbying.

For the three EU institutions alone the score is slightly higher at 36 percent, but still well below the ideal mark.

At 55 and 53 percent respectively, Slovenia is the only country and the EU Commission is the only institution to surpass the 50 percent mark. In both, whereas transparency and integrity measures are found to be relatively solid, the measures’ reach, implementation and enforcement are, however, found to be lacking.

The study finds that only 10 of the 19 countries assessed have some form of lobbying register.

In six (Austria, Ireland, Lithuania, Poland, Slovenia, the United Kingdom), this is a national mandatory register. Yet while mandatory, lobbying, its targets and activities are found to be too narrowly defined – indeed none of the 19 countries are found to have adequate definitions across the board.

The UK Lobbying Act (2014), for example, is estimated by the Association of Professional Political Consultants to only be able to capture around one per cent of those who engage in lobbying activities – this is due to its narrow targets focus on ministers, permanent secretaries and special advisers – but not on members of parliament or local councillors, the staff of regulatory bodies, and private companies providing public services.

In 14 countries, voluntary registers may apply only to select institutions, such as the National Assembly and Senate in France, in the Netherlands, and the EU Transparency Register, or to target sub-national level institutions, such as the Italian regions of Tuscany, Molise and Abruzzo, or Catalonia in Spain.

These registers’ voluntary nature fails to fully and accurately capture the real extent of lobbying, and through use of non-user-friendly data formats and through weak or non-existent oversight and sanctions, their potential as transparency, integrity and equality of access tools is further hindered.

Another finding of the report is that much of the influence in Europe is exercised through informal relationships away from the public eye, such as through corporate hospitality events, all paid expense business trips, gala dinners, or quiet drinks in parliamentary bars.

Lobbyists in Hungary told of their travels alongside international business delegations and visits to football matches. Lobbyists in Milan told of how they catch politicians in the Alitalia’s lounge in Linate’s Airport, while they wait to catch their flight to Rome.

Below the radar by design, such interactions are likely to fall through any regulatory net.

The study highlights also how particular groups enjoy privileged access to decision makers. With the largest sums of money spent, the pharmaceutical, finance, energy and telecoms sectors tend to dominate the lobbying landscape. In 2012, the official figure for spending by the pharmaceutical sector alone was 40 billion Euros, however the study suggests a more realistic number for the sector would be 91 billion Euro.

That Goldman Sachs recently increased their declared lobbying expenses does seem to corroborate that official figures tend to err on the conservative side.

The study also warns that with an increasingly intertwined relationship between politics and business, known as the ‘revolving door’ between public and private sectors, is posing serious risks of regulatory and policy capture.

Although a cooling-off period before former public officials can lobby their former colleagues is in place in most countries, the report finds that none of the 19 EU countries have effective monitoring and enforcement of such revolving door provisions.

One example cited is that of France. Since 2013 French legislation requires a three-year cooling-off period between the end of a public service mandate and a role within a company that the official previously had interactions with as part of his or her mandate.

In practice, effective monitoring is likely to be impeded by the very limited resources available to monitoring bodies, such as the Public Service Ethics Commission, versus the scope of their monitoring responsibilities – for the Public Service Ethics Commission this is over some 5.5 million public officials. And with MPs also being exempt from such cooling-off period, such legislation shows room for improvement.

When it comes to equality of access to decision makers, in 17 of the 19 EU countries assessed public officials are required to promote citizens’ participation through consultations, indicating that public engagement is paramount.

Yet although formal mechanisms to collect a variety of voices do exist, none of the countries are found to have measures in place that can show whose voices decision makers ultimately take into account. Measures that ensure a balanced composition of advisory groups — key in preventing cases like this – are only found in Portugal.

The report however does also praise some regulatory improvements that have occurred, such as the recently adopted lobbying law in Ireland, and the progress made in a number of countries — namely Bulgaria, Cyprus, Estonia, France, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, Slovakia and Spain — towards regulating not just lobbying but also its parallel act of political financing.

Yet, while such developments are positive and welcome steps in the right direction, the study warns that transparency, integrity, and equality of access remain overall rather elusive in lobbying regulation in Europe, and that while many voices seek a chance to shape political debates in ways that take their own interests into account, when it comes to influencing decision makers it is the well-resourced corporate interests that reach the most ears.

Overall, a lack of a EU-wide mandatory lobbying register on one side, and the presence of mostly voluntary and generally poorly designed, implemented and/or enforced national codes of conduct on the other, are enabling lobbying to continue to take place below the radar, so that we don’t really know who is lobbying whom, for what, and with what resources.

The study calls for lifting such veils of secrecy and the opening of lobbying to public scrutiny as the first steps towards promoting a fairer system in which a plurality of voices have equal access to political agenda-setting, and in which decisions ultimately are made so that people are put before profits.

Analysis by Annalisa Dorigo

Images from the Transparency International report