The fourth plenary session of the 14th central committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CPC) that took place between Oct. 20-23, 2014, has paved the path for a series of retrials of former misjudged cases, including the case of Huge Jiletu. Huge was sentenced to death and immediately executed after a violent inquisition process in 1996. The sentence came only 62 days after the rape and murder incident, of which, as it turned out, Huge was falsely accused. On Dec. 15, 2014, 18 years after Huge’s execution, he was acquitted by the Supreme People’s Court of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region.

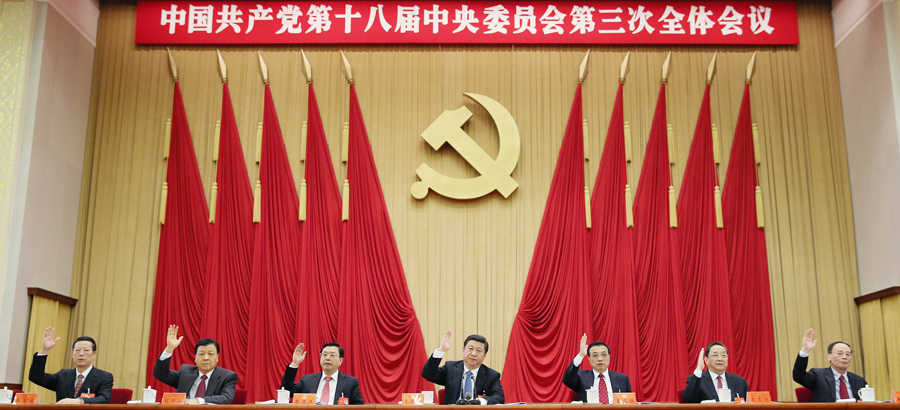

The main theme of the fourth plenary session is the “rule of law.” President Xi Jiping’s anti-corruption campaign targeting major CPC officials has been the topic of discussion on international media, official and social media in China, and at the dinner table of ordinary Chinese people for the past two years. The newly promoted strategy and doctrine, the “socialist rule of law with Chinese characteristics,” appears to be a natural step forward to a further systematized rule of the CPC dominated government. But the meanings of the official report lie deep beneath the surface of the centrality of administration by law, and demands deciphering. Among many clues, a most telling one might be that the promoted “rule of law” still falls under the leadership of CPC. The report utilizes a rhetoric that separates the communist party and the CPC leading government by stating that the leadership of CPC remains above the Law, and yet, the government should be law-abiding.

The fourth plenary session, however, has brought misjudged legal cases in the past into the daylight. Huge’s case, for instance, had the chance to surface and be given a retrial on the Supreme Court of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, the province where the case was first tried. Unlike 18 years ago when the case was closed with the conviction of Huge without sufficient evidence, this time Huge was finally given his long deserved exoneration. The change of the original sentence was based on the incompatibility of the confessed means of crime and the autopsy report, the lack of exclusivity based upon the results of the blood test, and finally, the inconsistency of Huge’s confessions on different occasions.

Notably, a man named Zhao Zhihong was arrested for rape and murder in 2005, and at the time had already confessed to be the true offender in the 1998 rape case. But the demand from Huge’s parents for a retrial of their son’s case, for reasons unknown never reached the Supreme Court. It forced Huge’s parents to continue appealing to higher authorities for the unsealing of the case. The case, however, remained sealed until the fourth plenary session of the CPC, and all of a sudden, at the new sweeping campaign of the “rule of law,” fell in the spotlight of legal debates.

Eighteen years ago, Huge and his friend found a naked woman’s body in a public restroom. They reported to the local police, and the 18-year-old Huge was immediately arrested by the police as a suspect in the crime. The case was tried in a rushed manner. Within a short period of only 62 days, Huge was sentenced to death and was immediately executed. The reason for such a hasty trial had much to do with the political campaign of the Chinese government at the time—local governments were told to crack down on criminal cases. The predecessor of the campaign was initiated by Deng Xiaoping in 1983, with its slogan being “quicker and stricter.” The direct outcome of such campaigns was careless and heavy sentences in the short run, and disparity between laws for the campaign and the “normal laws” in the long run.

This kind of political campaign bears similarities with the “War on Drugs” in the 1970s and 80s in the United States. What often happens is the appearance of stricter administration, plus a higher efficiency in resolving crimes, obscuring the reality of “quick,” “rigid” and often times unfair judgment. But does a society eliminate crimes with harsher, hastier punishment? Or does it create space for governance that is casual and authoritative?

Moreover, the appeasing effect of a stricter administration comes from the public’s fear of disorder in the society. In both the case of China in 1983 and 1996 and the United States in the 1970s and 80s, the rise of crimes on the street coincided with the rise of unemployment rates of certain communities and the polarity of wealth in the society. Since the 1980s China has been in a process of radical urbanization, which created a large number of migrating workers in the city. These workers from the countryside became the most easily discriminated population by law and by social welfare, and many of them turned to other means of making money when the option of selling cheap labor became unavailable. The cracking down on crime not only did not help in alleviating the actual social problems, but it aggravated the inequality between poor and rich communities by covering it up.

Huge’s case also sheds light on the question of the death penalty in China. To what extent is a government justified in the kind of violence that it itself criminalizes? It is not just a question of politics and governance, but also of the irreversibility of the act of killing: when a person is put to death, a retrial retrieves only justice, but not the life that is already lost.

Analysis by Joel Levi

For an English translation of the official report of the fourth plenary session of the 14th central committee of the CPC:

http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/language_tips/news/2014-10/24/content_18795510.htm

Other sources:

http://news.sina.com.cn/c/2014-12-31/134931348804.shtml

http://www.nmg.xinhuanet.com/xwzx/2014-12/15/c_1113639596.htm

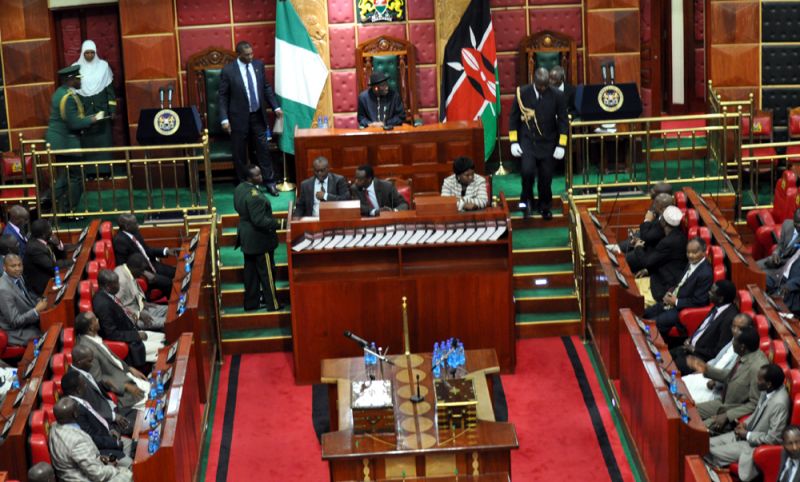

to play the next time. The flashy Nairobi bishop has since maintained that she will battle it out with other aspirants for Nairobi gubernatorial candidate come 2017. Among her opponents will be the flamboyant Nairobi senator, Hon. Mike Sonko and Nairobi businessman Jimnah Mbaru, who have both vowed to ensure she sinks into political oblivion. Indeed someone could be signing her political oblivion certificate by herself.

to play the next time. The flashy Nairobi bishop has since maintained that she will battle it out with other aspirants for Nairobi gubernatorial candidate come 2017. Among her opponents will be the flamboyant Nairobi senator, Hon. Mike Sonko and Nairobi businessman Jimnah Mbaru, who have both vowed to ensure she sinks into political oblivion. Indeed someone could be signing her political oblivion certificate by herself.