Although mountain glaciers around the world are melting at increasing rates in our warming climates, at least one range is unaffected. Pakistan’s Karakoram range, the highest point in Pakistan and the source of much of the water of the Indus River, is not melting–and scientists expect that it will not melt, but may put on snowmass in coming years.

Scientists are not sure why Karakoram range is not melting. An early theory was that the range was covered in rubble that may have had an insulating effect.

But now, researchers at Princeton University think they may have a better answer: seasonal weather patterns.

In their recent report, “Snowfall less sensitive to warming in Karakoram than in Himalayas due to a unique seasonal cycle,” the scientists credit Karakoram’s snowmass retention to temperatures that never rise enough to melt mountain glaciers–all year round.

Although most of the Himalaya’s experience heavy summer rains stemming from the South Asian monsoon, which far outweigh winter snows, this is not the case in Karakoram, where cold winter winds from Central Asia bear most of the precipitation. The South Asian monsoon seldom reaches Karakoram–it is uniquely blocked by the Great Himalayan Range to the south.

Although most of the Himalaya’s experience heavy summer rains stemming from the South Asian monsoon, which far outweigh winter snows, this is not the case in Karakoram, where cold winter winds from Central Asia bear most of the precipitation. The South Asian monsoon seldom reaches Karakoram–it is uniquely blocked by the Great Himalayan Range to the south.

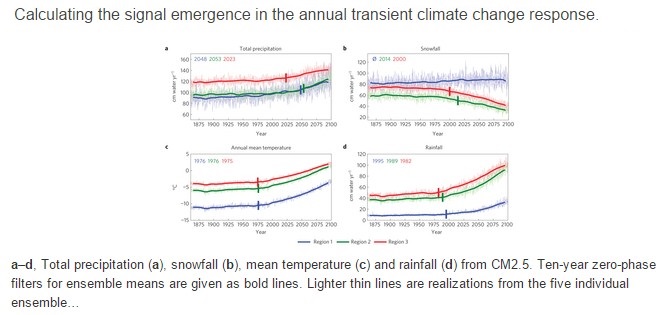

Investigating Karakoram for data has been a challenge. The topography of the area is extreme. K2 and three other pinnacles exceed 8,000 meters. In the past, researchers relied on average altitudes for the region, but the Princeton study used high-resolution maps and monthly precipitation data to create climate model simulations from 1861 to 2100.

While Karakoram does experience some warming in summer, the higher slopes were too cold in summer for glaciers to melt, the researchers found.

While Karakoram does experience some warming in summer, the higher slopes were too cold in summer for glaciers to melt, the researchers found.

Not only are the glaciers and snowmass above 4,500 meters not melting, the scientists expect them to remain until at least 2100, which is good news for Pakistan.

The range provides water to most of Pakistan through the Indus River. Although snow and ice at lower altitudes will melt, these declines will be offset by the higher cold. The cold upper regions provide water at a controlled rate, rather than the boom-bust cycle of flood and dry associated with sudden melts.

The rest of the Himalayas are bound to melt too, the researchers believe. They expect sharp glacial declines in coming years.

“Something that climate scientists always have to keep in mind is that models are useful for certain types of questions and not necessarily for other types of questions,” said Sarah Kapnick, a postdoctoral research fellow in Princeton’s Program in Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences and lead researcher on the work. “While the IPCC models can be particularly useful for other parts of the world, you need a higher resolution for this area.”

By Sid Douglas