In a first-of-its-kind study undertaken by University of California researchers, elite bargainers–those responsible for making today’s most important policy and business decisions–were examined to find out if they, like other people, reject low offers even when those offers involve benefits. The research is expected to offer increased understanding of some of the problems faced in global economic and environmental dialogues.

“Professionals, who had a lot of experience in high-stakes bargaining, played even further from the predictions of classic economic models. Concerns about fairness and equity aren’t expunged by experience, and persist in a group of very smart and successful professionals,” Dr. Brad LeVeck, Assistant Professor at the University of California, Merced, and lead author of the study, told The Speaker.

“Most experiments in human behavior are conducted on convenience samples of university undergraduates. So, when experimental results go against the assumptions in classic models from economics, many researchers are skeptical about whether those results will translate to the real world,” LeVeck told us.

“Inexperienced students at a university might just be making mistakes that more experienced professionals would avoid. At least when it comes to bargaining, our study shows that this isn’t the case.”

LeVeck’s study used a unique sample of 102 US policy and business elites who had an average of 21 years of experience conducting international diplomacy or policy strategy.

The names of the participating elites were withheld in order to mitigate possible false behavior that could have resulted from concern about harm to their reputations.

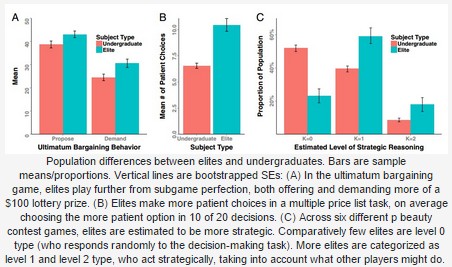

When participants bargained over a fixed resource–in the study the samples played “ultimatum” bargaining games that involved the division of a fixed prize, but the researchers had global agreements on international trade, climate change, and other important problems in mind–the elites actually made higher demands and refused low offers (below 25 percent in the share of a prize) more frequently than non elite bargainers. But elite bargainers also offered more.

“In our study, it wasn’t just the case that elite policy makers rejected low offers more often than the general public,” LeVeck said. “It was also the case that they made more generous offers.

“So, to a certain extent, these individuals have the right intuition about how to conclude a successful bargain. This suggests that considerations of equity and fairness are already taken into consideration by real world policy makers.”

Elites with more experience and age were found to bargain for higher gains all around.

“Our best evidence indicates that this finding is related to their professional experience… This could be because policy makers accommodate the possibility that low offers will be rejected, and therefore also learn that it’s generally ok to reject low offers.”

The positions from which the most important policy and business decisions are made, the researchers concluded, are occupied by elites who have either changed towards high demand bargaining or have been selected by some process that favors this type of elite.

Why bargainers reject low offers and why elite bargainers play for higher stakes are questions that are still unanswered. Past research has given weight to arguments that bargaining actions are not due to motives such as fairness, equity, or toughness, but may have more to do with spite, culture and social learning.

“Our study wasn’t designed to disentangle these explanations,” LeVeck said. “So, it’s difficult to know whether the people who reject low offers are individuals that intrinsically care about fairness for everyone, or are simply individuals who spitefully reject low offers (but would take more for themselves if it were possible). In the later case, people would care about fairness for themselves, but not for everyone. I suspect both of these motivations exist and affect the behavior of different people.”

The researchers considered other motives for elite bargaining tactics, such as future opportunities, other bargaining partners and power relationships, but those did not play into the experiments.

“I do think these types of complex, real-world considerations shape professionals’ intuitions about how to bargain,” said LeVeck. “However, other parts of our study show that policy and business elites think carefully about strategic decisions. This makes it less likely that these individuals were misapplying a lesson from the real world when they played the bargaining game in our study.”

The researchers pointed out that the study encourages a reappraisal of aspects of international cooperation, such as bargaining with regards to trade, climate and other world issues.

“Analysts and researchers are understandably skeptical when leaders complain that an agreement is unfair. It’s very plausible that the complaint is just ‘cheap-talk’: When pressed, those leaders should actually accept any agreement that is inline with their self-interest.

“By contrast, our findings raises the possibility that these complaints are more than cheap talk. Policy and business elites have some willingness to reject inequitable offers.

“So, when formulating proposals on issues like global emissions reductions or trade policy, leaders should pay attention to whether the other side will reasonably regard the deal as fair.”

The report, “The role of self-interest in elite bargaining,” was completed by Brad L. LeVeck, D. Alex Hughes, James H. Fowler, Emilie Hafner-Burton, and David G. Victor, and was published on the PNAS website.

By Sid Douglas