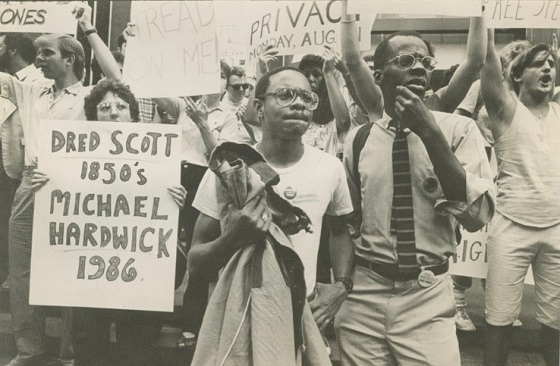

In the 80s and 90s, laws against homosexual activity were first upheld as not in violation of Constitutional rights and later reversed as being in violation–Bowers v. Hardwick (1986) and Lawrence v. Texas (2003).

In Bowers v. Hardwick, two Georgia men were arrested for sodomy when a police officer tasked with serving a warrant for public drinking found the men engaged in sex at Hardwick’s home. After the local district attorney decided not to proceed with the case, Hardwick brought suit against the Attorney General of Georgia, Michael Bowers, seeking a declaration that the state’s laws against homosexual sex were invalid. The ACLU wanted to try the case. The district court found for the Attorney General, the appeals court reversed this, and the case proceeded to the Supreme Court.

The result was that the Supreme Court found against Bowers in a 5-4 decision. The court found no constitutionally protected right to engage homosexual sex and upheld the Georgia statute as valid. Justice White wrote the majority opinion, which cited historical precedents condemning homosexual sex.

The dissenting opinion was written by Justice Blackmun (although Blackmun has since revealed that it was in fact his clerk who primarily authored the dissent), who disagreed with the majority’s focus on homosexual activity, writing that the case was no more about a right to engage in sodomy than Stanley (1969) was about a right to watch obscene movies or Katz (1967) was about a right to place interstate bets from a telephone booth; these cases, Blackmun contended, were about “the most comprehensive of rights and the right most valued by civilized men,” namely, “the right to be let alone,” quoting Justice Brandeis in Olmstead (1928). Blackmun continued, “Unlike the Court, the Georgia Legislature has not proceeded on the assumption that homosexuals are so different from other citizens that their lives may be controlled in a way that would not be tolerated if it limited the choices of those other citizens,” and stated that his finding was that the Georgia law under which Bowers was being tried was broad enough to also reach heterosexual couples engaging in anal or oral sex.

“(A) A person commits the offense of sodomy when he performs or submits to any sexual act involving the sex organs of one person and the mouth or anus of another. . . .”

“(b) A person convicted of the offense of sodomy shall be punished by imprisonment for not less than one nor more than 20 years. . . .” (Georgia Code Ann. § 16-6-2 [1981])

Blackmun wrote:

“Only the most willful blindness could obscure the fact that sexual intimacy is ‘a sensitive, key relationship of human existence, central to family life, community welfare, and the development of human personality,’ Paris Adult Theatre I v. Slaton (1973); Carey v. Population Services International (1977). The fact that individuals define themselves in a significant way through their intimate sexual relationships with others suggests, in a Nation as diverse as ours, that there may be many ‘right’ ways of conducting those relationships, and that much of the richness of a relationship will come from the freedom an individual has to choose the form and nature of these intensely personal bonds.”

Blackmun pointed not to a specific right to engage in homosexual activity, but to broad principles that have informed the treatment of privacy in specific cases. Blackmun held that the same protections that defended liberty and privacy interests in those other cases should apply in Bowers.

Blackmun again referred to Brandeis in Olmstead:

“The makers of our Constitution undertook to secure conditions favorable to the pursuit of happiness. They recognized the significance of man’s spiritual nature, of his feelings and of his intellect. They knew that only a part of the pain, pleasure and satisfactions of life are to be found in material things. They sought to protect Americans in their beliefs, their thoughts, their emotions and their sensations.”

At the time of Lawrence v. Texas (2003), it was illegal in 13 states to engage in consensual homosexual sex–this number was down from 25 at the time of Bowers, although it has been noted that a certain pattern of nonenforcement with respect to consenting adults acting in private had existed. That number was in turn down from 50 before 1961.

Lawrence and a man visiting his house were arrested on the night of September 17, 1998 outside Houston, Texas, when a jealous rival called in a false police report about “a black male going crazy with a gun” in Lawrence’s apartment. After contradicting accounts of homosexual activity by the arresting officers, the two men were charged and pled no contest to “homosexual conduct.” The jealous lover pled no contest to filing a false police report and was sentenced to 30 days in jail.

Lawrence et al. opted neither to plea their innocence nor to accept a minor fine and criminal charge, but to take on the law that outlawed, in effect, homosexuality.

By pleading no contest, Lawrence at al. waved their right to a fair trial, but asked the court to dismiss the charges on the basis of the unconstitutionality of the anti-sodomy laws. Lawrence claimed that because the law prohibited sodomy between homosexual couples, but did not prohibit sodomy between heterosexual couples, the law was unconstitutional under Fourteenth Amendment equal protection grounds:

“All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

After being denied the Fourteenth Amendment defense motion in their first trial, Lawrence appealed, and the Texas Fourteenth Court found that the Texas law violated the 1972 Equal Rights Amendment of the Texas Constitution (sec. 3):

“All free men, when they form a social compact, have equal rights, and no man, or set of men, is entitled to exclusive separate public emoluments, or privileges, but in consideration of public services.

Equality under the law shall not be denied or abridged because of sex, race, color, creed, or national origin. This amendment is self-operative”. (Added Nov. 7, 1972.)

The Appeals court found the law unconstitutional, but a year and a half later reviewed the case en blanc and reversed the decision, finding the law constitutional. Lawrence petitioned the Supreme Court, asking the Court to consider:

1. Whether the petitioners’ criminal convictions under the Texas “Homosexual Conduct” law—which criminalizes sexual intimacy by same-sex couples, but not identical behavior by different-sex couples—violate the Fourteenth Amendment guarantee of equal protection of the laws?

2. Whether the petitioners’ criminal convictions for adult consensual sexual intimacy in their home violate their vital interests in liberty and privacy protected by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment?

3. Whether Bowers v. Hardwick should be overruled?

The Supreme Court, which examined the case in terms of “the validity of a Texas statute making it a crime for two persons of the same sex to engage in certain intimate sexual conduct,” found that consenting adult homosexuals had a right to sex in their homes. The Texas law, which outlawed “any contact between any part of the genitals of one person and the mouth or anus of another person; or… the penetration of the genitals or the anus of another person with an object” (§21.01[1]), was unconstitutional, violating the Fourteenth Amendment Due Process Clause, the Court found.

Justice Kennedy wrote the majority opinion, in which he criticized the judgement of Bowers and placed Lawrence in a tradition of Constitutional interpretation with Griswold, Eisenstad, Roe, Planned Parenthood, Bowers and Romer, framing a narrative of progressive application of Amendment guarantees to privacy protections regarding human rights. The majority viewed Bowers this way:

“[T]he Court’s failure to appreciate the extent of the liberty at stake. To say that the issue in Bowers was simply the right to engage in certain sexual conduct demeans the claim the individual put forward, just as it would demean a married couple were it said that marriage is just about the right to have sexual intercourse. Although the laws involved in Bowers and here purport to do no more than prohibit a particular sexual act, their penalties and purposes have more far-reaching consequences, touching upon the most private human conduct, sexual behavior, and in the most private of places, the home. They seek to control a personal relationship that, whether or not entitled to formal recognition in the law, is within the liberty of persons to choose without being punished as criminals. The liberty protected by the Constitution allows homosexual persons the right to choose to enter upon relationships in the confines of their homes and their own private lives and still retain their dignity as free persons.”

The court looked to determine “whether the petitioners were free as adults to engage in the private conduct in the exercise of their liberty under the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution.” The majority found that they were. The court sought to find if any valid state claims existed that would pass the strict liability test. According to the majority opinion:

“The Texas statute furthers no legitimate state interest which can justify its intrusion into the personal and private life of the individual.”

A 6-3 decision stuck down the Texas law. The court overturned Bowers v. Hardwick.

“Bowers was not correct when it was decided, and it is not correct today. It ought not to remain binding precedent. Bowers v. Hardwick should be and now is overruled.”

Kennedy offered an opinion on privacy in general and the court’s opinion on homosexual sex regarding Lawrence particularly:

“Liberty protects the person from unwarranted government intrusions into a dwelling or other private places. In our tradition the State is not omnipresent in the home. And there are other spheres of our lives and existence, outside the home, where the State should not be a dominant presence. Freedom extends beyond spatial bounds. Liberty presumes an autonomy of self that includes freedom of thought, belief, expression, and certain intimate conduct. The instant case involves liberty of the person both in its spatial and in its more transcendent dimensions.

“The present case does not involve minors. It does not involve persons who might be injured or coerced or who are situated in relationships where consent might not easily be refused. It does not involve public conduct or prostitution. It does not involve whether the government must give formal recognition to any relationship that homosexual persons seek to enter.”

* * * * *

The differing interpretations of Amendment guarantees and reliance on other informative sources such as caselaw, moral codes, and traditional attitude towards various groups of people or activities in Bowers and Lawrence show a lack in the U.S. Constitution to provide expected human rights protections for homosexuals.

In Bowers, the dissenting opinion of the Court followed, expanded and extended interpretations of Amendment guarantees found in Griswold (1972) and Eisenstadt (1972) to sexual privacy rights for homosexuals. The majority disagreed, however: it found that there was no Constitutional protection for homosexual sex. But this opinion based its decision on a tradition of condemning homosexuality.

This decision was overturned in Lawrence, but the Constitutional basis was questionable. In Lawrence‘s 6-3 decision, five justices believed the statute violated Fourteenth Amendment Due Process Clause and one–who had been in the Bowers majority–believed it violated rather the same Amendment’s equal protection guarantees.

The majority opinion explained that “the case should be resolved by determining whether the petitioners were free as adults to engage in the private conduct in the exercise of their liberty under the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution,” and sought to find what the Due Process Clause protected. Kennedy’s opinion listed a progression of Court interpretations of Amendment guarantees in a sort of narrative scheme of liberating rulings, starting with Griswold and proceeding through Eisenstadt and Roe to Planned Parenthood to Bowers and Romer.

Griswold recognized the right of privacy in the home of married people and Eisenstadt extended the protection to unmarried couples for any procreative (or not) sexual activity. Eisenstadt had based this right on the Equal Protection Clause. Although the Lawrence Court favored the Due Process Clause as a basis for protection, Justice Kennedy quoted Brennan in Eisenstadt for an extension of privacy protections to homosexuals:

“It is true that in Griswold the right of privacy in question inhered in the marital relationship …. If the right of privacy means anything, it is the right of the individual, married or single, to be free from unwarranted governmental intrusion into matters so fundamentally affecting a person as the decision whether to bear or beget a child.”

The basis of this protection in the Due Process Clause was argued as false by many dissenters. Justice Scalia wrote:

“Though there is discussion of ‘fundamental proposition[s],’ and ‘fundamental decisions,’ nowhere does the Court’s opinion declare that homosexual sodomy is a ‘fundamental right’ under the Due Process Clause; nor does it subject the Texas law to the standard of review that would be appropriate (strict scrutiny) if homosexual sodomy were a ‘fundamental right.’ Thus, while overruling the outcome of Bowers, the Court leaves strangely untouched its central legal conclusion: ‘[R]espondent would have us announce … a fundamental right to engage in homosexual sodomy. This we are quite unwilling to do.’ Instead the Court simply describes petitioners’ conduct as ‘an exercise of their liberty’-which it undoubtedly is-and proceeds to apply an unheard-of form of rational-basis review that will have far-reaching implications beyond this case.”

An oral argument at Lawrence‘s Supreme Court trial questioned the propriety of protecting any consensual adult sexual activity in the privacy of a home, stating,

We have laws in states, like the one at the Supreme Court right now, that has sodomy laws and they were there for a purpose…. And if the Supreme Court says that you have the right to consensual sex within your home, then you have the right to bigamy, you have the right to polygamy, you have the right to incest, you have the right to adultery. You have the right to anything…. It all comes from, I would argue, this right to privacy that doesn’t exist in my opinion in the United States Constitution, this right that was created…in Griswold… .”

By Day Blakely Donaldson

Sources:

Justicia

Justicia

L&SJ (American Bill of Rights)