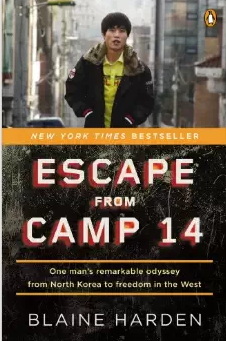

Dong-Hyuk Shin, the only North Korean prison camp escapee, revealed that the inaccurate details in his autobiography “Escape from Camp 14” were neither lies nor confusion about his memories following his traumatic experiences. He just wanted to keep some painful experiences to himself.

“First of all, let me tell about the controversial issues surrounding my book, as some people are still regarding me as a liar. For what and how would I make up those horrible memories? I just wanted to hide a part of my life in the book. Isn’t that a choice I am free to make?” Shin said.

According to the book, Shin underwent torture in North Korea’s most notorious political prison camp, No.14, at the age of 13. He later corrected this claim, however, to say that it was actually in Camp 18, known to be less controlled, when he was 20 years old, after moving out of Camp 14 at age six. Shin was transferred back to Camp 14, again, so he escaped from No. 14 in the end.

He said that he also had to correct the inaccurate report about his confession from United States media. The author of his book, Blaine Harden added in a new forward of the e-book that, “Trauma experts see nothing unusual in this.”

Shin, however, strongly denied the loss of memories, as Harden explained. “I didn’t forget any of the memories of my life. In reality, I couldn’t forget them even if I tried. Every time I tried to erase those terrifying moments, they remained in my head more clearly,” he said.

The prison camp survivor has undergone a tough time since the end of last year, when he arrived in South Korea. Last October, North Korean authorities produced a video called “Lie and Truth” to attack Shin, who had given evidence of North Korea’s human rights violations in front of the UN Commission of Inquiry. In the video, Shin’s father — whom he believed to be dead — contradicted his story.

“I found out that my father was still alive when I watched the video. I believed that he died in the prison camp where he was transferred. When I saw him in such a ridiculous video for the first time, I wasn’t happy at all, but I felt despair. I thought that he would’ve rather died than lived, because I can imagine how much he suffered and is still suffering tortures in the country because of me.”

The video and the presence of his father ultimately made him reveal what he did not explain in the book. Amid condemnation from many people, he could not stand the criticism of other North Korean defectors.

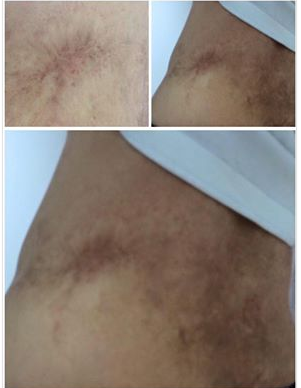

“I didn’t care about the South Korean media that only focused on the numbers, such as Camp 14 and 18 and my age, while ignoring the scars of prison camp torture on my body. But I was very sad and even enraged because of other defectors who had suffered in North Korea like me,” he continued.

“Some of them denounced me by showing the video produced by North Korean government. I felt miserable, as they didn’t know my true intention, which was to save the dying. I think that they might be jealous of my fame and money. But to be honest, I didn’t earn any money while working for human rights. And the fame had nothing to do with my life, since many North Koreans are still being killed. If I knew that my story would have gained this much fame at that time, I would’ve disclosed every single detail to the writer.”

He alluded to discontinuity in the campaign on his Facebook page this January, but a month later he restarted it.

The prison camp survivor has been involved in North Korean human right activity since 2007. But recently he has felt that everything that he has done was in vain, as nothing has changed yet compared to eight years ago.

“I started this campaign desperately to save tens of thousands of maltreated North Korean residents, because I was also one of them. I didn’t have time, as people were dying every second.”

He was particularly skeptical about the UN’s inquiry into the human rights situation in North Korea, launched in 2013.

“For what did the United Nations establish the Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in North Korea? What did they do for North Korean residents? It took more than one year for the UN General Assembly’s Human Rights Committee to adopt the resolution. What is next, then?

“I gave all evidence to them in order to save my family and friends — not to lay flowers on their graves. I don’t think that the officials of the UN would understand how serious the real situation in North Korea is, because most of them have not lived that kind of a desperate life.”

The 33-year-old activist begged people to see the invisible reality: “When I told my story to the UN, at first they asked me whether I could prove it,” he said.

“Six million Jews died in the Holocaust over the course of about three years. Who imagined that many people were killed in that short a time? It is exactly same as 70 years ago. We can’t see what is happening in North Korea, but the fact is that people are being publicly executed at this very moment.”

Despite of his sense of futility over his human rights campaign, he said that he will never give it up.

Currently, Shin is planning two projects for the near future. “I’m thinking to publish a magazine about ordinary South Koreans’ lives and to send them into North Korea through the Chinese border with North Korea,” he said.

Similarly, South Korea’s activist groups, led by North Korean defectors, have sent anti-North propaganda leaflets, attached to large balloons, from near the border for several years. This activity, however, escalated tensions between the two Koreas, and North Korean authorities even threatened South Korea with military action.

“North Korea’s sensitive reaction indicates that these flyers are quite influential in society. I chose to produce a magazine to describe South Korea more specifically. I would like to feature photos of couples holding hands, drinking coffee in the cafe, and walking freely in central Seoul. And I wish North Koreans could realize that they also have a right to live like that.”

He said that the second project is a bit more personal. “I’m aiming to make a video that rebuts every part of the video ‘Lie and Truth,’ before a conference at the United Nations in Geneva this September,” he said.

Through the video, he is hoping to send two messages to the North Korean government. “My ultimate goal is to enter North Korea with a delegation to the UN, and I want to visit Camp 14 where I was born and lived. If I can do that, no one will dispute my life, and finally I can prove the human rights violations,” he said.

The other message seems to be more important for In-Gun Shin — that was the original name of human rights activist Dong-Hyuk Shin.

“I’ll request the authorities let me meet my father either in North Korea or in a third country before he dies. And firstly, I’ll ask him why I was born in the prison camp. I then will say ‘I love you’ to my father for the first and last time.”

Photo and article by EJ Monica Kim