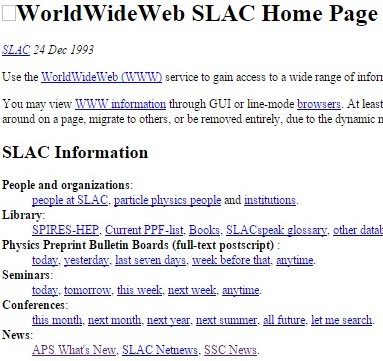

Digital archaeology that has revealed the earliest signs of web-life in America. Stanford Libraries has brought to light the first websites ever uploaded in the US–genealogically part Euro-descendant, part US original. The pages are now available for browsing, and Stanford Wayback, a customized platform for accessing archived web assets, provides a third dimension for viewing the internet, allowing users to see and navigate the web as it has changed over time and to look back in time at code written by the earliest “WWW Wizards.”

“A handful of staff at SLAC who worked on the early web fortuitously saved the files, along with their timestamps,” said Nicholas Taylor, web archiving service manager for Stanford Libraries.

The earliest site dates back to Dec. 6, 1991–a month in which no-fly zones were being set up in Iraq after the Gulf War, the Ukrainian people voted for independence from the Soviet Union and the Cold War ended, Hezbollite (Shiite Muslim) militants released their last US hostages, and Michael Jackson and Whitney Houston won at the 2nd annual Billboard Music Awards.

The sites were installed on the first server outside of Europe, which was installed by physicist Paul Kunz between Dec. 6 and Dec. 12.

Taylor told The Speaker how in launching the Stanford Web Archive Portal, once they learned of the existence of the earliest US websites, this seemed the most intriguing choice.

Taylor told The Speaker how in launching the Stanford Web Archive Portal, once they learned of the existence of the earliest US websites, this seemed the most intriguing choice.

“A major focus for Stanford University Libraries’ web archiving effort is preserving Stanford University’s institutional legacy. We thought that the SLAC earliest websites would be the most broadly interesting historical web content related to the University with which to launch the Stanford Web Archive Portal. That is to say, we didn’t explicitly set out to track down the oldest US website, per se, but became quickly interested once we learned about it.”

The lineage of the earliest US sites is a part European descendant-part original strain, Taylor told us.

“They’re necessarily derivative, in some sense; what made the Web was adherence to a common set of conventions (e.g., the syntax for a hyperlink). The SLAC ‘WWW Wizards’ built the first US website based upon the conventions formulated by Tim Berners-Lee, the creator of the world’s first website at CERN. In another sense, the first U.S. website was entirely home-grown, built foremost to serve the research needs of the SLAC research community.”

Taylor elaborated on this piece of digital archaeology was undertaken.

“You might say that there were two major digital archaeology efforts. One, SLAC’s previous recovery and preservation of the original website files, and two, Stanford University Libraries’ much subsequent restoration of access to the websites in their original temporal context, via the the Stanford Web Archive Portal.

“You might say that there were two major digital archaeology efforts. One, SLAC’s previous recovery and preservation of the original website files, and two, Stanford University Libraries’ much subsequent restoration of access to the websites in their original temporal context, via the the Stanford Web Archive Portal.

We have the early sites back online today because of SLAC staff foresight.

“Essentially, SLAC staff that were involved with the early websites and, later, staff in the SLAC Archives and History Office had the wherewithal to retrieve, set aside, and document the files constituting the earliest websites,” said Taylor.

The sites were saved with their timesstamps, which are associated with the first version of a website, as well as subsequent versions.

“The original timestamps were preserved as part of the SLAC backup system for those servers and are a critical piece of context in understanding the restored content.

“We’re accustomed to thinking about the Web in two dimensions–i.e., as a flat plane that we navigate spatially. Web archives and the Memento protocol, in particular, offer the prospect of adding a third dimension to the Web–allowing users to see how it has changed over time and seamlessly navigate to archived versions of resources that have since disappeared.”

Taylor commented on the nature of investigating the origins of the digital realm, and noted that we are close enough in time to still touch its ancestry.

Taylor commented on the nature of investigating the origins of the digital realm, and noted that we are close enough in time to still touch its ancestry.

“A last note about ‘digital archaeology,'” said Taylor, “unlike much archaeology, our digital archaeology effort had the benefit of being able to confer directly with the individuals who created these artifacts.”

Taylor encouraged everyone to support and celebrate the efforts of this “memory institution,” and take a look at our digital past in the artifacts they have recently preserved.

Stanford Wayback is part of the Libraries’ web archiving initiative, which aims to collect, preserve and provide access to web content that is at risk of being updated, replaced or lost.

By Andy Stern