PARIS — Women of the night and their artistic impact is the subject of a major exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. The show focuses on prostitution seen through the eyes of painters between 1850 and 1910. This extraordinary undertaking, whose title is borrowed from Honoré de Balzac’s controversial novel ‘Splendeurs et Misères des Courtisanes’ (The Splendours and Miseries of Courtesans), aims to unveil the faces and bodies of prostitutes as a genuine and rich source of inspiration for the painters of the period.

The mid-nineteenth century generated an effort to depict a concrete contemporary reality with a new desire to reject Romantic modes of idealization in art and literature which opened a new range of subject considered worthy of representation. The prostitute’s body as the ultimate anti-academic subject matter previously considered socially inappropriate could eventually be brought in the frame and became emblematic of the modernist gaze. Widely represented across canvas and texts, prostitutes became a symbol for modernity and embodied modern life itself.

From Van Gogh, Manet to Picasso or Munch, the exhibition features various generations of painters across several countries. As already suggested by its title, the exhibition also intends to examine the contradictory connotations of disgust and beauty associated with prostitution. Yet if some artists emphasized the ‘misery’ of it in their work while others chose instead to highlight its ‘splendour’, artists were all operating under the prism of fascination. Whether as cubists, impressionists, postimpressionists or expressionists, all were trying with a particular brush to reveal this disorienting world of the unseen sometimes lugubrious, sometimes colourful, no matter the technique of representation.

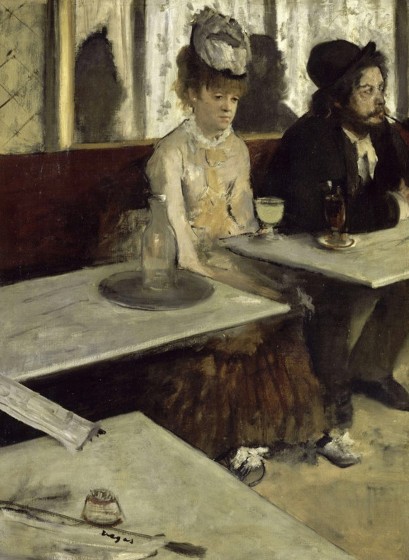

As they were experimenting and looking for new pictorial ways of representing prostitution, the subject was treated very differently depending on the painter’s artistic vision. Rather than reproducing scenes accurately and realistically, painters like Edgar Degas or Constantin Guys based their visions mainly on fantasies, suggesting and sublimating the noisy brothel atmosphere through unconventional techniques. Some chose to paint the common spaces of prostitution such as streets, harshly illuminated rooms or the dark interiors of ‘cafés-concerts’ and ‘music-halls’, while others preferred the intimate details of a face or a body.

Along with its artistic impact, the event also examines the social and cultural aspect of prostitution through Salon painting, decorative arts, sculpture and photography. In addition, various documentary and archival materials made available to the public highlight the ambivalent status of prostitutes from the splendour of the ‘demi-mondaine’, a pleasure girl living on her wealthy clients, to the misery of the ‘pierreuse’, an often clandestine street walker.

The social subject of prostitution is still a complex one nowadays. The fact that the Musée d’Orsay decided to conclude the year with a celebration of artistic images of prostitution has a particular resonance in light of the latest debates on the subject in France. We cannot but connect it to the recent decision of the French senate to scrap important sections of a government-backed law on prostitution that brought hundreds of prostitutes in the streets of Paris and other French cities last April. In spite of this resonance, whether taken as a subtle reminder of the still open debate on the controversial prostitution law in France or as a pure celebration of nineteenth century artistic imagery of prostitution, this impactful event is definitely not to miss.

‘Splendour and Misery — Pictures of Prostitution, 1850-1910’

22 September to 17 January 2016 – Musée d’Orsay, Paris

‘At the Moulin Rouge’, 1892, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, The Art Institute of Chicago

‘Olympia’, 1863, Édouard Manet, Grand Palais, Paris

‘The Absinthe Drinker’, 1901, Pablo Picasso, Hermitage Museum, St Petersbourg

‘The Absinthe’, 1873, Edgar Degas, Grand Palais, Paris

‘Party at the Moulin Rouge’, 1889, Giovanni Boldini, Grand Palais, Paris

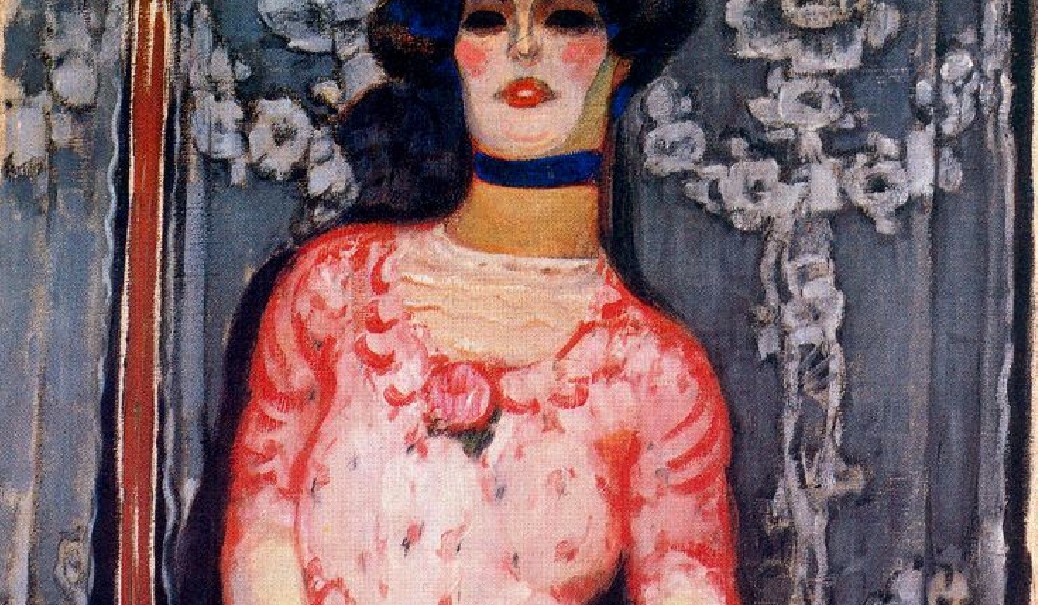

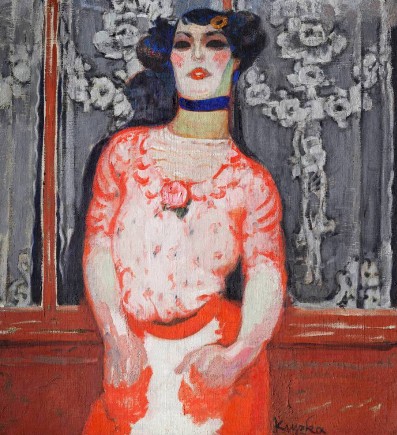

‘The Gallien Girl’, 1910, Frantisek Kupka, Národni Galerie, Prague

‘Rolla’, 1878, Henri Gervex, Grand Palais, Paris

‘The Wait’, 1848, Jean Béraud, Musée d’Orsay, Paris

By Pauline Schnoebelen