Originally written for Radio Free Asia’s Mandarin service, Woeser’s “Ai Weiwei’s ‘Wing’ From Lhasa” was translated by volunteer Zhao Wencui (Whitman College), with help from Chas McKhann, and has been kindly provided via the Ai Weiwei Studio and originally published by High Peaks Pure Earth.

I am a native of Lhasa. Even though I have been living in Beijing for ten years, I always go back and spend a few months in Lhasa every year. The three months that I spent there in 2013 were especially meaningful because I discovered “feathers” for Ai Weiwei’s “Wing” while I was taking photos of ruins in the Old Town and having Tibetan costumes made for him at three (Tibetan-owned) tailor shops. Those “feathers” and those Tibetan costumes filled my busy days with meaning but must have baffled the plainclothes cops who always followed me around.

The Tibetan Plateau sticks high into the sky and enjoys abundant sunshine, Lhasa is known as “the City of Sunlight”. Many households there have installed solar stoves (called “nyima top” in Tibetan) in their courtyards or on the roofs of their houses to heat water and cook food. The heat needed to heat water or cook food is emitted by mirror-like reflective metal panels. They take two forms: the old-style which is round in shape, like the sun, and comparatively bulky and heavy, and the new-style which looks like two wings, foldable and easily disassembled. Ai Weiwei’s “Wing” makes use of the latter.

The ruins that I was photographing were from a monastery destroyed during the Cultural Revolution. They are the wounds of Lhasa, a marked brand of history, full of violence and the evidence of changes. They demonstrate the fragility of substance or so-called “impermanence” in Buddhism. Every time I went back to Lhasa, I always went there and took similar photos of the ruins. I was familiar with every corner of the place, like what Osip Mandelstam, the poet who was persecuted to death by the communist Soviet Union, wrote, “I have come back to my city. These are my own old tears, my own little veins, the swollen glands of my childhood.”

The ruins are hidden in the depths of the small lanes in the Old Town. They are known to few outsiders, but are symbols of existence for the locals. The neighborhood where the ruins are located used to be the living quarters for hundreds of monks and now is home to more than 80 households of local Tibetans, Tibetans from remote areas, Han migrant workers, and Muslim business venders. The courtyard of the ruins used to be the site for grand religious ceremonies and now is full of solar stoves, shining in the sun, like wide-open wings.

I took a photo that shows an aluminum kettle being heated on the stove, with steam coming out; an old Tibetan woman is sitting next to the stove sunbathing; she looks ponderingly at something and her fingers are resting on the prayer beads; behind her are lines hung with drying clothes of different colors, and several strings of worn prayer flags; all the lines and strings are tied to the broken doorposts of the ruins; the flags are dancing in the breeze and the dripping wet clothes are weighing down the lines. Everything about this photo displays the normality of everyday life.

I like posting my photos on Twitter and Facebook. I have several tens of thousands of fans on Twitter, but, of course, Ai Weiwei has far many more than I do. We started to show mutual interest in each other’s work a long time ago. He made brilliant remarks on my photos of Lhasa by saying: “conquering fear is like taking medicine, one dose at a time. Year after year, Allen Ginsberg took a picture of his kitchen window, but there was always a change.” He encouraged me and said: “Take as many photos as possible. Life is precious, but raw reality is also valuable. Your photos can conquer fear, remember the past, witness the times of savagery, and at the same time redeem you.” Then he noticed the shining solar stoves in front of the ruins and asked me if I could purchase some for him. That was the start of the story of “Wing”.

First, I thought he just wanted one “wing”. I went to a small shop on a street in the Old Town to make inquiries, and was told that a new one cost about 400 Yuan. But it was too new, and new “wings” lack something. After thinking a bit, I asked Ai Weiwei: “How about a used one? One that has been shined by the sun of Lhasa, boiled the water of Lhasa, and mirrored the silhouette of Tibetans? I can buy a new one and exchange it for a used one with a local Tibetan. How does that sound?”

Ai Weiwei replied: “Yes, I’d prefer used ones. Get as many as possible. Several dozen would be okay. It would be even better if you could get the used kettles and pans to go along with the stoves.”

I pushed him about what type of used stoves he wanted: rusty ones, faded ones, or mottled ones?; and as for kettles and pans, just used ones or ones that were burned black?; deformed ones or ones in their original forms? He laughed and said that he preferred the most worn ones I could find, but entreated me to make sure that there would be no new scratches or damage added during transportation.

But it was a big problem for me to ship those “wings” to Beijing from Lhasa. Those “wings” are made of metal and each of them weighs more than 100 pounds. I myself cannot even carry one. I thought and thought, and recalled that a friend of mine had a big courtyard, and also a vehicle with tools. Most importantly, he was a native of Lhasa and knew where to go and how to exchange new “wings” for old, and how to handle the shipping. Moreover, he used to work as a carpenter and could make boxes for shipping those “wings”. Thus, I shifted the whole job to him and told him to take it as a contract and to deal with the generous Ai Weiwei directly.

Thereafter, within a very short time, one batch after another of those “wings” which had been bathed by the sun, the rain, the snow, the wind and the frost of Lhasa arrived in Beijing at 258 Caochangdi, Ai Weiwei’s workshop. Later, I went back to take pictures of the ruins again, and saw the new “wings” shining in the sun and the new kettles boiling with steam. It was a win-win situation! Besides, thanks to the increased demand for “wings” from Ai Weiwei, my friend to whom I had shifted the job and his relatives were all able to replace their old stoves with new ones. “If he needs more, I have to go to the countryside to get them,” said my friend.

Indeed, I didn’t realize that Ai Weiwei would need that many “wings”. They went from ten to twenty to fifty to sixty! I don’t remember how many he actually bought, and I didn’t know what kind of artwork he would use them for. In fact, I asked him about it, and he said he didn’t know either. I suppose that is typical for the creation of all his artwork: he was inspired to do something, but he didn’t really know what that creation was going to be, at least not back then. So we did nothing but wait, and anticipate. More than six months passed before anything happened. During this time, I left Lhasa and went back to Beijing. Ai Weiwei invited me to several dinners at Tibetan restaurants in Beijing. It was me who had introduced him to those restaurants, which made me feel like an ambassador who tried to promote Tibetan cuisine.

In October 2013, the French Indigène editions published my book on Tibetan self-immolations, “Immolations in Tibet: The shame of the world”.

As a matter of fact, long before the story of “wings”, there had been another story about the self-immolation of Tibetans. One hundred and twenty-six male and female Tibetans (147 to date) had immolated themselves out of sacrifice or protest. I documented the life stories and achievements of each, and wrote a book about them. In that book, as best that I could, I interpreted, sympathetically analyzed, and frankly criticized the self-immolations that some Tibetans had continuously committed over the years. Of course, what I criticized was the injustice of the Communist government and the silent masses who submitted to it. I caught sight of Ai Weiwei’s remarks about Tibetan self-immolation on Twitter: “Tibet is a hard case which questions human rights in China and in international communities and the standards for justice that no one can avoid or ignore. So far, no one has not been humiliated.” After reading this, I asked him to design the cover for my book to be published in Paris. Ai Weiwei replied: “The meaning of self-immolation behavior, no matter from philosophical perspective or religious perspective, is beyond explanation or interpretation from the survivors because the public only sees the direct political reason responsible for its happening. But still I would like to try even though I understand very well that this is hopeless.”

The final design of the cover looks like this: the names of all the Tibetans who committed suicide by self-immolation are printed on it in Tibetan language; in the middle of the cover is a curling, blazing flame–full of beauty, not the miserable bitterness of the sacrificed; and the background color is plain and solemn. Ai Weiwei wrote in his email to me: “……I was struggling. I wanted to look at those sacrificed in a comparatively calm manner due to many factors, such as courage, intention, memory and my ignorance.” Honestly, I was very grateful to Ai Weiwei. I remembered him saying: “I haven’t been to Tibet. I would feel ashamed if I went there. I think the best way to respect Tibetans is to leave them alone and let them live independently. Don’t bother them.”

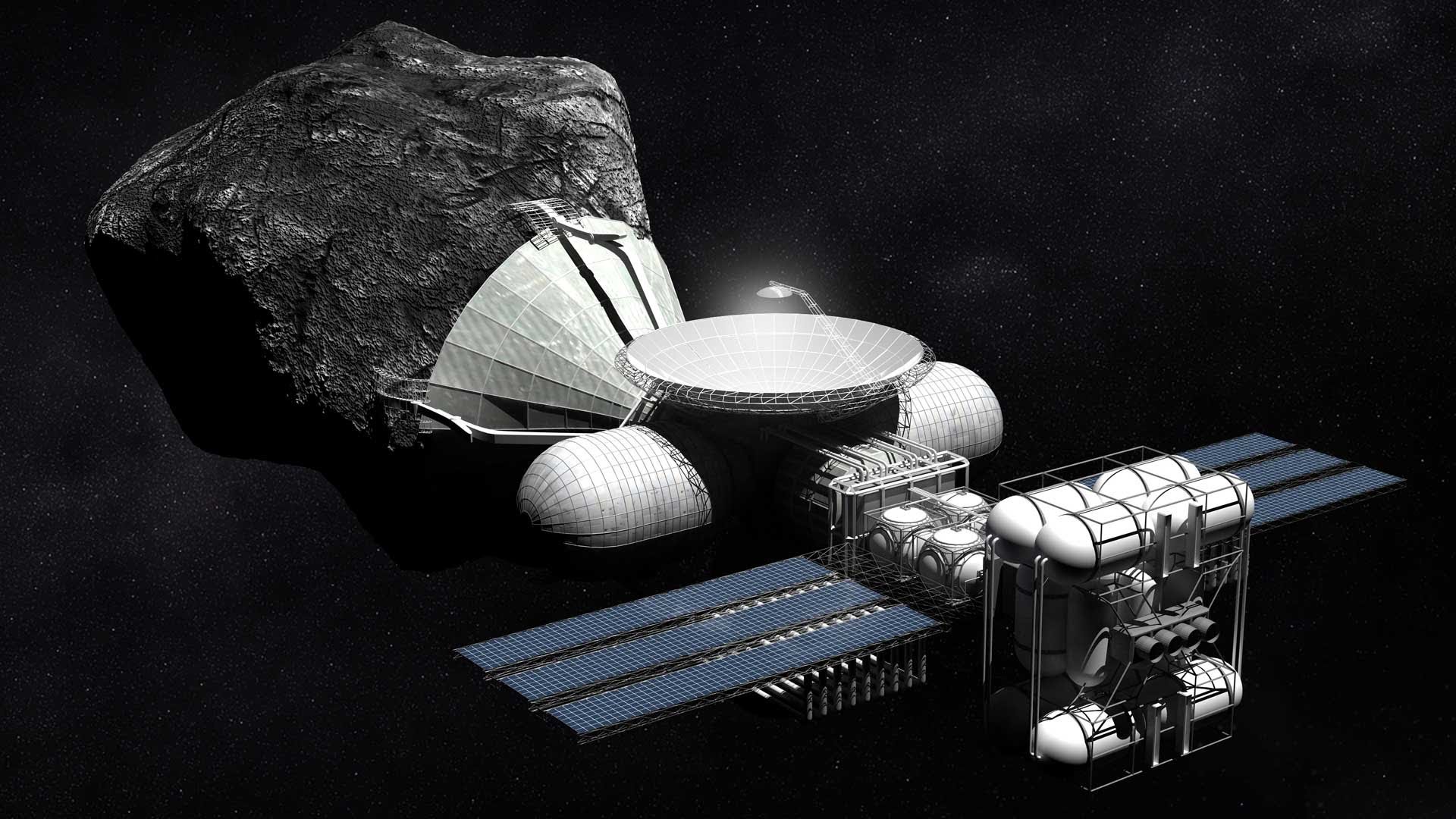

I want to say something about the “wings”, however. One day in September, 2014, I broke through the firewall as usual and was surprised to find out that the “wings” shipped from Lhasa to Ai Weiwei had crossed the ocean and were appearing on the infamous island of Alcatraz in the United States, as a part of an exhibition of his artwork. In this former federal prison that was used to lock up the most dangerous criminals, those solar stoves, like shining feathers, were put together and transformed into a huge metal “Wing” spread wide as if it wanted to break through the walls and fly away. It also carries several kettles that had been used to heat water for yak butter tea and pans that had been used to cook potatoes and yak meat. I could almost taste the familiar flavors!

“Wow, how brilliant that he has turned rotten and discarded things into something so amazing and miraculous,” I exclaimed, murmuring to myself.

I downloaded the photo of “Wing” and enlarged it on the computer screen and looked closely at every feather, as if I were trying to find out if those “wings” from Lhasa still bore the marks of Lhasa. And, yes, they do. The marks are still there and are like mirrors that reflect the changes of the times. Most importantly, having travelled a long way, those “wings” that were originally cooking stoves, have been transformed into a huge, spiritually meaningful Wing by Ai Weiwei. Though heavy (it is said to weigh more than 5 tons), it bears the flavor of Tibet. The Wing that has withstood the burning of the sun on the Tibetan Plateau, in union with the flame of life of those immolated Tibetans, symbolizes the human desire to pursue freedom and civil rights, just as the phoenix reborn from ashes spreads its wings and flies towards the light. This is my interpretation.

August 22, 2015